Summary

Advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized our knowledge of the transcriptome, leading to the discovery of multiple classes of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) across all kingdoms of life. While coding RNA mainly serves as a template for synthesis of protein, the ncRNAs carry out diverse regulatory functions and modulate gene expression at multiple stages mainly at epigenetic, transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and translational levels. Recent advances in plant research have revealed the potential of ncRNAs in various cellular processes, which includes growth and developmental aspects, vegetative to floral meristem transition, gametogenesis and response to unescapable environment factors like biotic and abiotic stresses. Hence, studying the ncRNA biology, their mode of action and its interaction with the binding proteins, greatly enhance our understanding and help in crop improvement programs. Characterizing and leveraging the potential ncRNAs to specifically modulate plant gene expression, provides a significant scope for improving and enhancing desirable traits. This review highlights foundational aspects of ncRNA biology, including their biogenesis and the diverse regulatory role of several ncRNA classes and discusses the recent discoveries that emphasize their essential roles in plant development and stress resilience, giving insight into their applicability in modern agriculture.

Keywords

Non-coding RNA, circular RNA, gene regulation, RNAi, epigenetic modification, crop improvement

Introduction

The central dogma of molecular biology illustrates the sequential movement of genetic information through the key processes of replication, transcription, and translation, in which deoxy ribonucleic acid (DNA) is copied, transcribed into messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA), and subsequently translated into protein. During transcription, RNA acts as a vital intermediary between DNA and protein synthesis. The RNA world hypothesis suggests that the life likely originated with a relatively unstable molecule, the RNA. Later, DNA which is a more stable molecule, took over as the principal carrier of genetic information and RNA was left with the role of a messenger [1]. Eventually, scientific advancement unravelled that RNA was also involved in dynamic modulation of gene expression pattern. Thus, RNA mainly contributes to establish cellular homeostasis, adaptation to stress conditions and overall functioning of organism through its unique catalytic activity [2].

Aside from mRNA, numerous forms of RNA have been identified and become prominent with the advent of modern techniques like high-throughput sequencing, microarray analysis, and transcriptomics. Since these RNAs are not directly involved in protein synthesis, they are classified as “non-coding RNAs” (ncRNAs). These ncRNAs were previously dismissed as transcriptional noise or cellular by-products, but now they have recognized as crucial regulators in cellular functions through experimental and computational studies [3]. The regulatory power of ncRNAs may be attributed to their distinct structural and functional properties, such as catalytic activity, reduced stability, and their capacity for precise interactions with DNA, RNA, and proteins [4].

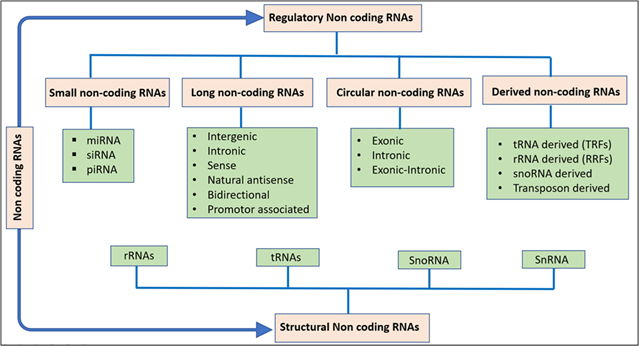

Several evidences prove that ncRNAs play essential roles in regulating the gene expressions by operating at genomic, transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational levels ultimately influencing the biological processes such as growth, cellular differentiation, and stress adaptation[5]. Moreover, ncRNAs are now emerging as promising biomarkers in disease diagnosis and also been used as therapeutics of human diseases [6]. Typically, ncRNAs constitute a diverse family of RNA molecules that are transcribed by various RNA polymerases, and these ncRNAs can be broadly classified as structural/ housekeeping/ constitutive and regulatory class. Constitutive ncRNAs are expressed constantly at high levels in all cells, which mainly participate in basic cellular processes such as translation and RNA processing [7]. This class of ncRNAs comprises ribosomal RNA (rRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), small nuclear RNA (snRNA), and small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA). Whereas the regulatory classes are usually expressed in a cell-type, stage-specific, or condition-dependent manner, functioning mainly to regulate gene expression [7] and are classified into small ncRNA (sncRNA), long ncRNA (lncRNA), circular RNAs (circRNA) and derived ncRNAs, the detailed classifications is presented in Figure 1.

Generally, the ncRNAs follow well-defined pathways that begin with activation by specific signals, followed by their biogenesis and are subsequently subjected to various modifications or processing steps. The mature ncRNAs execute their precise regulatory role in transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene silencing, translational repression, RNA stability, chromatin remodelling [5]. Additionally, to maintain homeostasis and prevent nonspecific regulations, ncRNAs are degraded once they are no longer required by the cell through cellular RNA turnover pathways [8,9] Although cells may generate a wide range of ncRNAs, not all of them are functional; hence may have no regulatory roles [3]. Therefore, differentiating the functional ncRNAs from the total RNA pool and elucidating their regulatory roles in developmental, physiological, and stress-responsive processes is highly important. Such comprehensive studies on ncRNAs provide better opportunities to exploit the functional ncRNAs as valuable tools for crop improvement. The present review basically describes the diverse regulatory classes of ncRNA, with an emphasis on their biogenesis and the molecular mechanisms underlying their regulatory functions in plants.

In addition, we highlight representative examples which illustrate the functional significance of ncRNAs along with the recent discoveries that enhance our understanding of their roles in plant development, stress adaptation, and crop improvement.

Historical significance

The discovery of ncRNAs started in 1939, when Torbjörn Caspersson and Jean Brachet independently showed that the cytoplasm is very rich

in RNA and its amount increases during protein synthesis [10]. This provided the first hint about the requirement of RNA during

protein synthesis, more importantly, acting as a link between DNA and proteins [1]. Later, in 1955, the first noncoding RNA (rRNA) was

discovered by Georges Palade, which is part of the very abundant cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex: the ribosome [11]. Two

years later, in 1957, the second class of ncRNAs was discovered by Mahlon Hoagland and Paul Zamecnik: the tRNA, which is an “adapter”

molecule for the translation of information from RNA to amino acid synthesis [12]. Further, in the late 1960s, other RNA groups in

structural class, such as heterogeneous nuclear RNA (hnRNA), snRNAs, as well as snoRNAs were discovered [1].

The first regulatory non-coding RNA, micF, was discovered in Escherichia coli in 1984 and became notable for its role in suppressing translation of the outer membrane protein F (ompF) mRNA by directly pairing with its ribosome-binding site through sense–antisense base interactions [13]. In the late 1980s, H19 RNA was identified as the first regulatory ncRNA discovered in eukaryotes. Initially, it was misclassified as mRNA due to the small open reading frame (ORF) present in the gene, but subsequent research revealed the absence of translation, establishing H19 as a non-coding, regulatory RNA [14]. The function of H19 as an RNA molecule remained a mystery until the functional characterization of another lncRNA, X-inactive specific transcript (Xist) [15]. This discovery revealed that both H19 and Xist are involved in dosage compensation in mammals, a process that maintains balanced levels of X-linked gene products between sexes which is critical for cellular equilibrium [1].

During the early 1990s, researchers documented a molecular phenomenon in different kingdoms, for instance, “co-suppression” in plants, “posttranscriptional gene silencing” in nematodes, and “quelling” in fungi, all characterized by the inhibition of protein production through RNA-mediated silencing pathways. However, none suspected the RNA to be a key actor until the identification of the first micro RNA (miRNA) lin-4, in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans in the year 1993[16]. Later in 1998, Fire et al. (17) reported that exogenous double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) can explicitly silence genes by RNA interference (RNAi) mechanism. These discoveries led to the characterization of numerous small ncRNAs, which led to the establishment of two major categories: miRNAs, which regulate endogenous gene expression, and small interfering RNAs (siRNA), which protect genome integrity against foreign or invasive elements such as transposons, viruses and transgenes [18].

During the genomic era, with the onset of advanced technologies and robust NGS, together with extensive international consortiums such as the Functional Annotation of the Mammalian Genome (FANTOM) (https://fantom.gsc.riken.jp/) and the Encyclopaedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) (https://www.encodeproject.org/) it was concluded that 80 per cent of the DNA is transcribed into RNA yet only a meagre 1.5 per cent of that RNA is actually translated into protein in humans [1]. Extensive transcription activity fundamentally transformed scientific understanding of the transcriptome and sparked a growing interest within the research community, leading to the identification and characterization of numerous non-coding RNAs.

Small noncoding RNA

The sncRNAs are typically short molecules, ranging from 20 to 30 nucleotides in length. These small RNAs generally act as gene

expression inhibitors and are mainly involved in RNA silencing processes. In these mechanisms, mature sncRNAs serve as specificity

factor, directing effector proteins to their complementary nucleic acid targets via base-pairing interactions [18]. Among the various

classes of small RNAs, three major types hold key regulatory roles: miRNAs, siRNAs, and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs). Notably,

siRNAs and miRNAs are widely present across many species and physiological contexts, both originating from dsRNA precursors. In

contrast, piRNAs are found primarily in animals, function mostly in the germline, and are derived from single-stranded precursors

that are presently not very well understood.

Biogenesis of sncRNAs

miRNAs

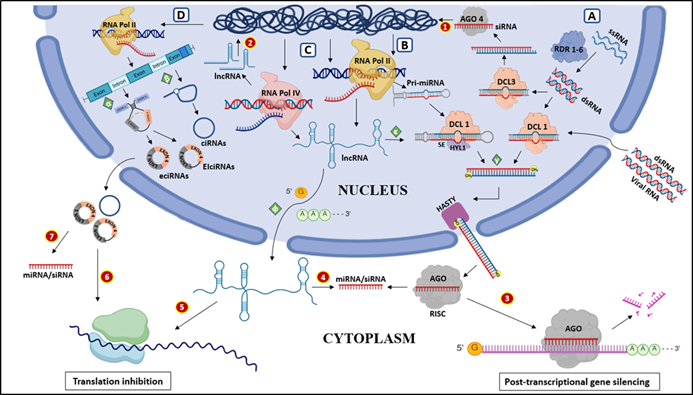

Plant miRNAs are endogenous ncRNAs that typically consist of approximately 20–24 nucleotides that play a key role in post-transcriptional

gene regulation. The biogenesis of miRNAs begins with the transcription of single-stranded primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) transcripts from

MIR genes by RNA polymerase II (Pol II). These transcripts fold into imperfectly paired stem-loop structures known as precursor miRNAs

(pre-miRNAs) [19]. The hairpin-shaped precursor is then processed into a miRNA–miRNA* duplex by the coordinated action of DICER-LIKE 1

(DCL1), the double-stranded RNA-binding protein HYPONASTIC LEAVES 1 (HYL1), and the zinc-finger protein SERRATE (SE) [20]. The mature

miRNAs are initially methylated by HUA ENHANCER 1 (HEN1) [21] and then exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm by the HASTY(HST)

export protein [22]. Finally, mature miRNAs associate with the Argonaute (AGO) protein and result in formation of the RNA-induced

silencing complex (RISC) [20]. Only one strand of the duplex is stably associated with an miRISC complex; usually, the miRNA strand is

more strongly favoured than the miRNA* strand, guiding it to complementary target transcripts (mRNA) [18]. Typically, they bind to the

3' untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs and can either degrade the mRNA or inhibit its translation, thereby controlling the

expression of specific genes (Figure 2B). (Note: * in miRNA represents the antisense strand of duplex form)

siRNAs

The siRNA can originate either exogenously from viral RNA and transgenes or endogenously from repeat-rich genomic regions, transposable,

and retro-elements [23]. In plants, depending on their origin and processing enzyme involved, siRNAs can be grouped into 7 subclasses;

the detailed description of each class is given in Table 1 [7; 24]

The generation of siRNA is primarily dependent on one of six RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RDR1–6) that copy single-stranded RNA

(ssRNA) to generate dsRNA. The dsRNA is then processed by DCL1–4 into sRNA duplexes: DCL1 mainly generates 18–21 nt sRNAs, while DCL2,

DCL3, and DCL4 produce 22-, 24-, and 21-nt sRNAs, respectively. Following processing, these duplexes are either retained in the

nucleus to regulate chromatin or exported to the cytoplasm, where they assemble with AGO proteins within the RISC to mediate

post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) (25; 26). Similar to the miRNA processing, only one strand of the siRNA duplex, the guide

strand, is selectively retained in the siRISC and the ‘passenger’ strand is discarded (Figure 2).

Regulatory role of sncRNAs

In plants, sncRNAs play a central role in regulating gene expression, primarily through the RNAi mechanism, which silences the target

gene at transcriptional level. The mechanism involves the loading of mature siRNA or miRNA into the AGO protein, resulting in the

formation of the RISC complex. The guide strand specifically base pairs with the target mRNA by complementarity and leading to the

initiation of mRNA degradation or inhibition of translation. Another important role of small RNAs, particularly siRNAs, is their

involvement in the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway, where they guide epigenetic modifications at specific genomic

location.

| siRNA Type | Size (nt) | Origin/Description | Processing Enzyme(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| cis-acting siRNA (ca-siRNA) | 24 | Derived from the same locus as their target RNA | DCL3 |

| trans-acting siRNA (ta-siRNA) | 21 | Produced from non-coding TAS gene loci; act in trans | DCL4, RDR6, AGO1 |

| heterochromatic siRNA (hc-siRNA) | 24 | Originates from heterochromatic/repetitive regions | DCL3, Pol IV, RDR2 |

| repeat-associated siRNA (ra-siRNA) | 24 | Produced from repetitive sequences (TEs, repeats) | DCL3, Pol IV, RDR2 |

| long siRNA (lsiRNA) | 30–40 | Found under stress; derived from long dsRNA | DCLs (exact type may vary) |

| phased siRNA (phasiRNA) | 21 or 24 | Produced in a “phased” manner from precursor transcripts | DCL4 or DCL5, RDR6, (miRNA trigger) |

| natural antisense siRNA (nat-siRNA) | 21–24 | Generated from overlapping sense–antisense transcripts | DCL1/2/3/4 (varies), RDR6 |

In RdDM pathway, the Pol IV and RDR2 help in generating the double-stranded precursor siRNA and upon processing by DCL 3, the precursor siRNA is cleaved into specific 24-nucleotide (nt) siRNA and loaded into AGO 4 (or AGO6/9). Simultaneously, Pol V produces scaffold lncRNA, and together they serve as a platform to recruit the AGO4–siRNA complex to trigger DNA methylation by DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASE 2 (DRM2) [27]. Thus, 24nt siRNA guides the DRM2 to the specific location where methylation is necessary. This process plays an important role in regulating developmental programs, facilitating stress adaptation, and ultimately contributing to genome evolution.

sncRNA in biotic stress

RNAi primarily regulates plant development by modulating gene expression at various developmental stages such as flowering,

vernalization, fruit development, formation of seeds, and other processes. RNAi plays a pivotal role in plant immunity against

pathogen attack, specifically in case of viruses. Naturally, plants produce several siRNAs and degrade the viral genome. However,

many viruses evolved to synthesize the silencing suppressor proteins that help in counter-attack the host RNA silencing machinery.

To overcome these challenges, transgenic methods have been deployed in several crops, where viral genes are expressed in the form of

antisense RNA, hairpin RNA (hpRNA) or intron hairpin RNA (ihpRNA). Upon expression, these constructs activate RNAi, leading to

enhanced resistance against viruses [28]. Notable successes include the development of the virus-resistant 'HoneySweet' plum

targeting plum pox virus genes [29], transgenic tomato lines producing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against the silencing suppressor

(NSS) gene of tomato spotted wilt orthotospovirus (TSWV) [30], and Nicotiana benthamiana plants expressing inverted hairpin RNA

targeting the helper component proteinase gene for resistance to papaya ringspot virus [31]. Collectively, the above reports

demonstrate that expressing small RNA precursor constructs effectively induces RNAi, conferring increased viral resistance in

plants.

In pest management, RNAi technology offers a novel and environmentally friendly method by selectively silencing critical genes in target pests [32]. This is achieved by delivering dsRNA into insect tissues, either by developing transgenic plants expressing specific dsRNA molecules or through external applications like dsRNA sprays. RNAi-based strategies have been successfully implemented against various insect pests, including Helicoverpa armigera, Diabrotica virgifera, and Leptinotarsa decemlineata, resulting in decreased pest survival and reduced crop damage. For instance, transgenic tomato plants expressing dsRNA constructs were developed, targeting crucial genes, Acetylcholinesterase 1 (AChE1) and SEC23, in Phthorimaea absoluta, which resulted in enhanced resistance against infestation [33]. Significant progress has also been achieved in improving dsRNA delivery methods to overcome degradation and enhance their uptake in insect system using several approaches. These include coating or complexing dsRNA with polymers, nanoparticle-mediated encapsulation and employing interpolyelectrolyte complexes (IPECs) or paperclip dsRNA; these strategies together improve the protection, delivery, and persistence of dsRNA in the insect system, thereby significantly increasing the efficacy of dsRNA sprays [34]. For example, the oral administration of an artificial diet consisting of dsRNA, which targets the Acetylcholinesterase-like protein (AchELP) and SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable 7 (SNF7) genes in Bemisia tabaci [35] and Leucinodes orbonalis [36], respectively, induced significant larval mortality, suggesting the potential role of dsRNA-based strategies as effective biopesticides.

RNAi has been successfully applied in managing fungal pathogens by targeting the essential fungal genes using two major strategies they are host-induced gene silencing (HIGS) and spray-induced gene silencing (SIGS). In HIGS, plants are genetically engineered to express dsRNA molecules against fungal virulence genes, which are subsequently taken up by invading pathogens during infection. SIGS, on the other hand, involves direct application of dsRNA sprays on plant surfaces, allowing uptake by fungal cells and silencing of target genes without the need for transgenic plants [37]. A few examples include the use of HIGS strategy to manage Magnaporthe oryzae by targeting pathogenicity and development genes to control rice blast disease [38], and using SIGS for the topical application of BcTRE1-targeting dsRNA (BcTRE1-dsRNA), which exerted a strong inhibitory effect against Botrytis cinerea, that was evidenced by significantly reduced fungal growth and lesion formation [39]. Although HIGS and SIGS approaches are effective they have certain limitations and challenges associated with commercial use. HIGS strategy requires stable genetic transformation of the host plant, which is technically challenging for many crop species, time-consuming and is classified under Genetically Modified Organism (GMO) technology, making it subject to strict, complex, and costly authorisation processes [40]. HIGS may not be considered as effective against certain types of pathogens, such as necrotrophic fungi that feed on dead host tissue, which cannot provide a sufficient, continuous supply of silencing RNAs [41]. Pathogens can potentially develop resistance to HIGS over time, for example, by evolving mechanisms to evade or suppress the hosts RNAi machinery. The complete mechanism by which silencing RNAs are secreted from plant cells and taken up by pathogen or pest cells is still unclear, making it difficult to optimize the process [42]. Meanwhile, SIGS bypasses the stringent regulatory process and is generally considered a non-GMO approach, as the dsRNA is an externally applied product that does not alter the host genome, and is regulated as a conventional pesticide or biopesticide [43]. Several limitations of SIGS include the instability of dsRNA in the environment and the variable efficiency of dsRNA uptake by target pathogens [44].

sncRNA in abiotic stress

Several evidence suggested that the dynamic regulation of small RNAs occurs during various abiotic stresses (Table 2). Examples

include the salinity-responsive miRNAs identified in Arabidopsis thaliana [45], Zea mays [46], the miRNA expression profiles in

response to drought are documented in Sorghum bicolor [47], Gossypium hirsutum [48] and chilling-responsive miRNAs have been

characterised in Glycine max [49] and Zea mays [50]. Leveraging this knowledge and modifying the expression profiles of target genes

holds great potential for developing crop varieties with enhanced resilience to adverse climatic conditions.

The advances in high-throughput sequencing and bioinformatics allow the discovery and functional analysis of novel sncRNAs, which guide targeted genetic improvement [57]. Current strategies, include use of tissue-specific promoters and genome editing tools to precisely modulate miRNA expression, which mainly assist to avoiding negative phenotypic effects. Recently, the new RNAi design, Loop ended RNA (ledRNA) exhibited stronger RNAi activity than traditional RNAi, and ledRNA-based gene expression regulation has been proven in diverse kingdoms of life such as plants, fungi and aphids [58]. Similarly, researchers identified the most effective small interfering RNAs (esiRNAs) and combined them into "effective dsRNAs." This innovative approach targets multiple viral strains simultaneously, offering broader and more potent protection against several viruses [59].

Presently, the regulatory status of exogenous dsRNA-biopesticides is not well established. There is a wide difference in perception on the application of exogenous dsRNA-biopesticides. For example, New Zealand has adopted a liberal stance, the USA and Australia have a moderate approach and the EU is stringent on regulatory approach [60]. The dsRNA in EU and Australia is considered as chemical pesticide. In Australia, it is regulated through APVMA and the OGTR [43], whereas in the EU, approval involves a two-step process: EFSA evaluates the active substance, followed by zonal assessment by Member States [61]. In USA, it is considered as a biochemical pesticide which requires EPA approval under FIFRA and FFDCA [62]. The regulatory or safety concerns associated with the RNAi mechanism, should be subjected to a robust safety assessment before commercial use. In plants, dsRNA can stimulate pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) independent of RNAi [63], and RNAi can trigger epigenetic changes such as RdDM. Hence, long-term risk assessments are essential, as RNAi products may show delayed efficacy or non-lethal phenotypes [64]. The regulatory framework must address environmental fate, non-target effects, and biosafety issues in order to declare RNAi as a secure, eco- friendly, and targeted alternative approach for crop protection [65]. However, the regulatory aspects related to the use of transgenic research will continue to fall under the GMO regulatory framework in different countries.

Long Non-coding RNAs

RNA molecules longer than 200 nucleotides which are involved in a regulatory role are categorized under lncRNA and found

ubiquitously in plants, animals, fungi, and prokaryotes. Although most lncRNAs are primarily located in the nucleus and associate

with chromatin, they can function in both nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. Many lncRNA functions are based on the capacity

to fold into secondary structures, which allows them to interact with other types of RNA, DNA, and proteins [66].

Biogenesis of lncRNA

Most plant lncRNAs are transcribed by RNA Pol II, which produces capped, polyadenylated transcripts. Additionally, in plants, certain

lncRNAs are produced by two unique RNA polymerases, Pol IV and Pol V, especially those linked to RdDM pathways [67]. Relative to the

genomic location, lncRNAs are divided into six subclasses: sense, antisense, long intergenic (lincRNA), bidirectional,

promoter-associated and intronic (Table 3) [68]. Many lncRNAs undergo typical co-transcriptional RNA processing like splicing. Some

lncRNAs are polyadenylated; however, non-polyadenylated lncRNAs also exist, especially those related to RdDM, which may be

synthesized by Pol IV or Pol V and often lack poly(A) tails (Figure 2C) [67].

Regulatory role of lncRNA

The important functions of lncRNA is to regulate gene expression mainly at epigenetic, transcriptional, post-transcriptional,

translational, and post-translational levels through diverse mechanisms. The main mechanism includes, association with chromatin

remodelling, activation of transcription, transcriptional interference, processing of RNA, and inhibition of translation process.

lncRNAs in epigenetic regulation

In case of epigenetic mediated gene regulation, the lncRNAs perform its function either by directly associating with histone-

modifying complexes, or acting as a scaffold molecule to regulate the histone modifications. The well-known plant lncRNA: COLD

ASSISTED INTRONIC NONCODING RNA (COLDAIR), was first to be discovered in plants, which are found to regulate methylation of histone

proteins in the chromatin region of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC). Under cold conditions, the COLDAIR helps in the recruitment of PRC2

complex to the FLC locus, this leads to accumulation of H3K27me3 and consequently, it accounts for silencing of FLC gene during

vernalization. The other mechanisms of lncRNAs are acting as molecular scaffolds in which they bind two or more protein molecules in

order to perform specific biological functions [69]. The lncRNA named AUXIN REGULATED PROMOTER LOOP RNA (APOLO) is a lincRNA,

transcribed by RNA Pol II, and modulate the PINOID (PID) gene expression by interacting with the PRC1 and PRC2 components. This leads

to the redeposition of H3K27me3 repressive marks at the promoters of APOLO and PID genes. Simultaneously, APOLO transcript

synthesized by Pol V produces a 24 nt siRNA, and help in recruiting the AGO4-siRNA complex to the chromatin region, subsequently the

chromatin modifiers attach to these complexes leading to the establishment of DNA methylation. Thus, chromatin loop changes occur in

the promoter of PID, which dynamically regulate the PID gene expression and further, modulate the auxin response pathway [70].In

another study, the same lncRNA APOLO regulates shade avoidance syndrome by dynamically modulating the three-dimensional chromatin

structure of key genes such as BRC1, YUCCA2, PID, and WAG2 [74].

| Sl No | sRNA (family) | Main target(s) | Species (example) | Role under abiotic stress | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | miR169 (miR169z) | NF-YA (NF-YA5) | Rice / Arabidopsis | Improves drought tolerance via NF-YA regulation and downstream metabolic adjustments. | [51] |

| 2 | miR395 | ATP sulfurylases (APS/ATPS), SULTR transporters | Arabidopsis / Tomato / Rice | Regulates sulfate assimilation and root development during sulfate deficiency; modulates stress responses linked to sulfur metabolism. | [52] |

| 3 | ta-siRNAs (TAS1/2/3/4) | Auxin Response Factor (ARF), MYBs, other transcription factors | Arabidopsis and crops | ta-siRNAs generated from TAS transcripts alter TF expression (e.g., ARFs) and modulate responses to nutrient stress, heat, and hypoxia. | [53] |

| 4 | miR156 | SPL transcription factors | Wheat, Alfalfa, Apple, Arabidopsis | Induction or overexpression improves drought and heat tolerance via SPL repression and enhanced flavonoid/ROS scavenging. | [54] |

| 5 | miR398 | CSD1, CSD2 (Cu/Zn SODs), CCS1 | Arabidopsis, Tomato, other crops | Temperature- and ROS-responsive miRNA that modulates antioxidant systems under heat and oxidative stress. | [55] |

| 6 | miR399 | PHO2 (ubiquitin E2-related) | Arabidopsis, Banana | Regulates phosphate homeostasis; responsive to phosphate starvation and heat stress through shoot-to-root signaling. | [56] |

A: Biogenesis pathway of siRNA, B: miRNA, C: lncRNA, D: circRNA; α: Generation of exonic circRNA and Exon-intron circRNA by backsplicing, β: Generation of intron lariat, which act as a precursor for circular intronic RNA, γ: Formation of miRNA-miRNA* duplex or siRNA-siRNA* duplex through cleavage by dicer enzyme. ε: lncRNA acting as a precursor for miRNA, φ: Upon transcription from RNA polymerase II, lncRNA either get capped and polyadenylated like mRNA or remains as it is without any modification; The important functions of ncRNAs. 1: The AGO-bound siRNA 4 participates in RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway, 2: The lncRNA generated from pol IV or V, functioning in RdDM, 3: The AGO-bound-miRNA or -siRNA complementarily base pair with its target mRNA and activation of PTGS mechanisms, 4: lncRNA acting as miRNA sponge, represses the miRNA activity, 5: lncRNA participating in translation inhibition, 6: circRNA functioning in translation inhibition, 7: circRNA acting as miRNA sponge. (ssRNA – single-stranded RNA, RDR- RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, DCL- Dicer-like enzyme, HYL1-Hyponastic leaves 1, SE: Serrate, AGO- sArgonaute, RISC-RNA-induced silencing complex, RNA pol II and IV- RNA polymerase II, and IV, ciRNA- circular intronic RNA, EIciRNA- Exon-Intron circular RNA, EciRNA- Exonic circular RNA)

| Enzyme | Organism | Location | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| FRE1 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Plasma membrane | Reduces extracellular Fe³⁺ for uptakea |

| FRE2 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Plasma membrane | Similar function as FRE1, with broader substrate rangea |

| Ferric reductase | Escherichia coli | Periplasmic/cytoplasmic | Reduction of ferric-siderophore complexesb |

| FRO2 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Root epidermis | Reduces soil Fe³⁺ for uptake under iron deficiencyc |

Similarly, a lncRNA LAIR, derived from the antisense transcript of leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase (LRK) gene clusters has been studied [71]. The overexpression of LAIR remarkably increases the H3K4me3 and H3K16ac at LRK1 locus, which helps in open chromatin structure. Further, LAIR was shown to associate with the chromatin-modifying complexes: OsMOF and OsWDR5. LAIR helps to co-localize these chromatin modifiers at the LRK1 genomic locus, accordingly increases the transcription of LRK1 and thus accounts for increased grain yield in rice [71]. In another study, the cold-induced lncRNA, MAS which is derived from antisense transcript (NAT) shown to activate the MADS AFFECTING FLOWERING4 (MAF4) by interacting with WDR5a. This leads to an increase in H3K4me3 histone marks on MAF4, which in turn suppresses premature flowering in Arabidopsis [72]. In rice, the lncRNA, RICE FLOWERING ASSOCIATED (RIFLA) which is transcribed from the first intron of the OsMADS56 gene found to specifically associate with H3K27 methyltransferase, OsiEZ1. Overexpressing RIFLA reduces the expression of OsMADS56 (a floral repressor), indicating that RIFLA and OsiEZ1 cooperatively suppress OsMADS56 expression by epigenetic pathway to promote early flowering in rice [73].

Transcriptional regulation

lncRNAs can directly target the DNA sequences and represses the transcription process. Additionally, they can associate with proteins,

mainly transcription factors and inhibit or activate the gene expression. Recently, a long intergenic noncoding RNA (lincRNA)

ELF18-INDUCED LONG-NONCODING RNA1 (ELENA1) was shown to activate transcription. The ELENA1 acts as a positive factor in increasing the

resistance against Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000. Knockout and overexpression studies revealed that ELENA1 affects the

expression of PATHOGENESIS-RELATED GENE 1 (PR1) gene by directly interacting with the mediator subunit 19a (MED19a). The level of

MED19a increases at the PR1 promoter region through ELENA1 interaction, impels the PR1 expression [75]. The inhibitory activity of

lncRNAs have also reported, for instance, lncRNA named SVALKA (SVK), which originated from antisense strand between C-repeat binding

factor (CBF) 3 and CBF1, participates in modulating the CBF1 expression level in cold stress. Mutant studies reported that

cold-induced CBF1 expression was repressed by SVK and this has biological link during cold acclimation and cold tolerance in

Arabidopsis [76].

lncRNAs in post-transcriptional regulation

The role of lncRNA has been reported in alternative splicing processes. In Arabidopsis, lncRNAs: ENOD40 and lnc351 were shown to

interact with nuclear specific splicing regulators known as nuclear speckle RNA-binding proteins (NSRs), which control alternative

splicing. lnc351 competes with mRNA for binding to NSRs, thereby influencing the alternative splicing of auxin-responsive genes

regulated by NSRs, which affects lateral root development [77]. Moreover, lncRNAs also modulate the gene expression patterns through

involvement of siRNAs and miRNAs. Some lncRNAs function as endogenous target mimics (eTMs), competing with miRNAs in a process called

“miRNA sponging,” and are referred to as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) [78]. For instance, the IPS1: a lncRNA acts as a ceRNA

during phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis, where 23-nucleotide conserved region of IPS1 mimics miR399 targets and binds to miR399

without degradation. This leads to inhibition of miR399 activity, as a consequence the expression of the PHOSPHATE 2 (PHO2) gene

increases to support normal growth under phosphate deficiency [79]. Similarly, in maize, the lncRNA PILNCR1 operates by the same

mechanism to respond to low phosphate stress [80]. In strawberry fruit ripening, the lncRNA FRILAIR regulates LAC11a expression by

acting as a noncanonical target mimic of miR397 [81]. The miR858 in Malus spectabilis inhibits MsMYB62-like, an anthocyanin repressor

transcription factor. Under normal conditions, lncRNAs, eTM858-1 and eTM858-2 serve as endogenous target mimics of miR858 and prevents

the cleavage of MsMYB62-like mRNA. The expression of these lncRNAs reduce significantly under low-nitrogen conditions, thus allowing

miR858 to suppress the MsMYB62-like more effectively, which ultimately enhances the anthocyanin production [82].

Additionally, some lncRNAs serve as precursors for miRNAs; for example, npc83 and npc521 in Arabidopsis produce mature miRNAs: miR869a and miR160c, respectively, while lncRNAs such as npc34, npc351, npc375, npc520, and npc523 are identified as precursors of 24-nucleotide siRNAs [83]. In addition, lncRNA can mediate decay of RNA, for example, a lncRNA 23468, which functions as a decoy for miR482b, reducing miR482b levels and thereby upregulating NBS-LRR resistance genes, enhancing resistance to Phytophthora infestans in tomato [84]. The lncRNA67 is shown to sequester miR3367 and prevent the interaction of miR3367 with GhCYP724B gene in fertile cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) line 2074B. In the cytoplasmic male sterile line 2074A, the absence of or reduced levels of lncRNA67 allow miR3367 to interact with the target GhCYP724B mRNA, which suppresses the expression and thereby reduces the GhCYP724B protein. This reduces the Brassinosteroids (BR) biosynthesis, resulting in male sterility [85].

lncRNAs in translational regulation

During the process of translation, lncRNAs are known to be recruited selectively to polysomes with the help of complementary base

pairing, which enhances or inhibits protein synthesis. In addition, lncRNAs can increase the translation process indirectly by

sequestering miRNAs [84]. In rice, the PHOSPHATE1;2 (PHO1;2) gene plays a crucial role in exporting phosphate into the apoplastic

space of xylem vessels. Under phosphate deficiency, the levels of cis-natural antisense transcript (cis-NAT) PHO1;2 a lncRNA, and the

PHO1;2 protein increase; although the mRNA levels of PHO1;2 remains unchanged. Modulating the expression of the lncRNA cis-NAT PHO1;2

either by downregulation or constitutive overexpression, results in a corresponding decrease or significant increase in PHO1;2 protein

levels without altering the expression or nuclear export of PHO1;2 mRNA. This indicates that cis-NAT PHO1;2 facilitates PHO1;2

translation by promoting its recruitment to polysomes, thereby helping to regulate phosphate homeostasis [86]. Additionally, global

analyses of polysome-associated RNAs and ribosome footprints in Arabidopsis have identified five cis-NAT lncRNAs, including those

associated with ATP BINDING CASSETTE SUBFAMILY G transporters: ABCG2 and ABCG20 and a POLLEN-SPECIFIC RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE 7 (PRK7)

family member, which are linked to nutrient uptake, lateral root development, and root cell elongation, respectively [87].

Currently, the databases such as PlantNATsDB—a comprehensive database of plant NATs, lncRNAdb—a reference database for lncRNAs, NONCODE—integrative annotation of lncRNAs, EVLncRNAs, PLNlncRbase, CANTATAdb, GreeNC—Green non-coding Database, RNAcentral — non-coding RNA sequences and PLncDB—plant lncRNA database, are used to deposit the lncRNA sequences. These databases serve as an important platform for the plant lncRNA community and provide a comprehensive resource for data-driven discoveries and functional investigations in plants [88].

Circular RNAs

CircRNAs are a unique group of single-stranded RNA molecules characterised by a covalently closed continuous loop, in which the 3′

and 5′ ends are joined together. The circRNAs were initially discovered in the 1970s within plant viroids, like the potato spindle

tuber viroid, where they appeared as covalently closed circular RNA molecules. In eukaryotic cells, circRNAs were first identified

in the 1990s in animal cells, but their widespread abundance and regulatory functions have only been elucidated recently due to

advances in high-throughput RNA sequencing technologies [89]. The size of circRNAs varies in organisms, ranging from 100 nucleotides

or less to over 4 kilobases. While traditionally classified as noncoding RNAs, recent evidence has shown that some circRNAs can encode

proteins and act as regulator of gene expression through influencing transcription and microRNA activities [90]. Predominantly

localised in the cytoplasm, circRNAs can be present at levels up to ten times higher than the associated linear RNAs from the same

locus of a gene. Their circular structure, lacking the free 5' and 3' ends found in linear RNAs, makes them resistant to exonuclease

degradation, resulting in greater stability within cells. circRNAs expression was known to be tissue-specific and cell-specific and

can be largely independent of the corresponding linear host gene expression. This suggests that the regulation of expression might be

crucial concerning control of its function [91].

Depending on the splice junction location in the genome, circRNAs are classified into three basic types they are exonic–intronic, exonic and intronic. However, studies have recently summarised 10 different types of circRNA [92]. Earlier reports suggest, the presence of antisense circRNA, overlapping circRNA, and sense overlapping circRNA in Triticum aestivum [93].

Biogenesis of circRNA

In general, circRNAs originate from exons closer to the 5’ end of a protein-coding gene and may consist of multiple or only a single

exon. Despite the fact that, the majority of circRNAs consisting of exons from protein-coding genes, and can also arise from introns or

intergenic regions, Untranslated regions (UTR) and ncRNA loci, including those from the locations antisense to known transcripts [94].

The formation of circRNAs happens generally through the backsplicing mechanism and alternate splicing (Figure 2D). Current research has

established that the canonical spliceosomal machinery is essential for back-splicing, with the process being supported by specific

protein factors and complementary sequence elements. The spliceosome catalyzes the typical eukaryotic pre-mRNA splicing by removing

introns and joining exons. However, the generation of circRNAs via back-splicing differs significantly from the conventional splicing

of linear RNAs. It is also distinct from other types of circular RNA formation, such as those produced by direct single-strand RNA

ligation, circularized introns, or intermediates from processed rRNAs [95].

In back-splicing, the downstream splice donor site is linked to an upstream splice acceptor site, in contrast to canonical splicing,

which joins an upstream (5’) donor site to a downstream (3’) acceptor site. This unique mode of splicing results in a covalently closed

circRNA and an alternatively spliced linear RNA missing some exons. Despite these differences, both canonical splice signals and the

spliceosomal machinery are required for back-splicing. Most highly expressed circRNAs originate from internal exons of precursor mRNAs

and often consist of multiple exons, suggesting that back-splicing generally occurs alongside canonical splicing [96]. Two main models

describe the mechanism behind back-splicing, mainly differing in which splicing event occurs first. The “exon skipping” or “lariat

intermediate” model proposes that canonical splicing initially skips certain exons, producing a linear RNA and a long intron lariat

containing the skipped exons, which then forms a circRNA via back-splicing. Alternatively, the “direct back-splicing” model suggests

that circRNAs are generated directly by back-splicing, producing an exon-intron(s)-exon intermediate that either degrades or is

processed into a linear RNA with skipped exons. While further biochemical studies are needed to fully clarify these mechanisms, it

seems both models can operate in living cells [97].

Regulatory role of circRNA

The most captivating feature of circRNA is its stability. The circular nature of 5′-3′ back spliced or 2′-5′ linked RNA is stable for

more than 48h, as evidenced by its resistance to exonuclease activity when compared to linear RNA which possesses a half-life of less

than 10h. Even though circRNAs constitute only 1 per cent of total RNA in the cell, it can be detected due to its longer stability

[98]. Analyses of multiple RNA-seq datasets reveal that circRNAs are conserved across various species in both animals and plants [99].

Moreover, the expression patterns of circRNAs are specific to particular tissues, isoforms, and developmental stages, as observed in

rice [100]. The interaction between circRNAs and RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) can either sequester RBPs away from their typical

functions or allow circRNAs to act as RBP sponges. Exonic circRNAs predominantly reside in the cytosol, while intron-retaining

circRNAs, such as exon–intron circRNAs and intronic circRNAs, are mainly found in the nucleus. Similarly, circRNAs containing retained

introns, like intron–intergenic circRNAs, are believed to localize in the nucleus as well [101].

Increasing evidence highlights the potential involvement of circRNAs in responses to stress in plants. Their expression varies in

reaction to different biotic and abiotic stresses, including nutrient deficiency, intense light, heat, cold, drought, and salinity.

However, the specific regulatory mechanisms and biological functions of circRNAs under these stress conditions remain incompletely

understood. For example, stress-induced circRNA expression has been documented in rice during copper tolerance [102], in wheat under

drought stress [93], and in grapevine during cold tolerance [103]. CircRNAs were initially reported under biotic stress in Arabidopsis

during pathogen interactions [104] and have since been found in other crops, for instance, the circRNAs are differentially expressed

in kiwifruit in response to pathogen invasion [105]. Specifically, 584 circRNAs showed defined expression patterns during Pseudomonas

syringae pv. actinidiae infection, correlating with different infection stages. Network analyses have further identified circRNAs

linked to plant defense responses [105]. Additional studies demonstrated that circRNAs act as negative regulators in response to tomato

yellow leaf curl virus in tomato [106], play a crucial role in cotton’s defense against Verticillium wilt [107], and contribute to

maize’s response to maize iranian mosaic virus infection [108]. circRNAs are also recognized as important regulatory molecules in

plant developmental processes [109]. To support this, miRNA target mimicry was validated by overexpressing the circRNA Os08circ16564

in a transgenic rice line. This circRNA was predicted to act as a target mimic for canonical miRNAs from the miR172 and miR810

families, which play key roles in the development of rice spikelets and floral organs [110]. In Arabidopsis, an increase in circRNA

expression linked to porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism, as well as hormone signal transduction, has been observed during leaf

senescence [111]. Another study showed that a circRNA derived from the sixth exon of the SEPALLATA3 (SEP3) gene acts in cis by binding

to its own DNA locus to form an R-loop, which causes transcriptional pausing and elevates levels of alternatively spliced SEP3

transcript variants, leading to pronounced floral homeotic phenotypes [112]. Further detailed research into the regulatory roles of

circRNAs in plants will enhance our understanding of their functions and foster their potential application in crop improvement.

Transfer RNA-derived fragments (tRFs)

The tRFs are generated either from the processing of precursor tRNAs or from the cleavage of mature tRNAs by specific endonucleases.

These fragments, also known as tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs), tRNA-derived RNA (tDRs), or stress-induced RNAs (tiRNAs). Typically,

tRFs are 13 to 40 nucleotides in length and have been recognized as important regulators in cellular processes. Initially, tRFs were

thought to be mere degradation by-products; however, their accumulation is regulated since defective tRNAs are targeted for

degradation through adenylation signals [113].

Based on the length and the position of cleavage on the mature tRNA or pre-tRNA, the tRFs are classified as type I, type II and tRNA

halves. Type I and II tsRNAs, ranging from 18 to 30 nucleotides in length, originate from cleavage on mature tRNA and pre-tRNA,

respectively. The type I tsRNAs are further divided into two subgroups: 5′tsRNA (tRF-5 or 5′tRF) and 3′tsRNA (tRF-3 or 3′tRF), which

are derived from the 5′ and 3′ ends of mature tRNA, respectively [114]. Type II tsRNAs (tRF-1 or 3′U tRF) 16–48 nt in length are

processed from a 3′ trailer sequence of pre-tRNA that begins 1 to 2 nt downstream of the 3′ end of the tRNA genomic sequence [115].

tsRNAs of length 30–40 nt are called “tRNA halves” because their lengths are almost half that of mature tRNA. They are often referred

to as “tiRNA” due to their stress-induced characteristic. Additionally, other types of tsRNAs that are not included in the classes

described above, are i-tRF, referred to as tRF-2, with a variable length and is derived from the internal region of mature tRNA

straddling the anti-codon region. Another type begins at the 5′ end of the leader sequences in pre-tRNA and ends in the 3′ terminus

of the 5′ exon in the anti-codon loop after removal of introns [116].

Biogenesis of tsRNA

The different classes of tsRNAs are synthesized by different processing enzymes. Growing evidences suggest that type 1, 18- to 30-nt

tsRNAs are processed by endonucleases, for instance, LysTTT3′tsRNA is processed by angiogenin (ribonucleases) in mammals [117] and

Rny1p, a RNase known to process tsRNA in yeast [118], whereas in case of plants, RNase T2 is responsible for the production of tsRNAs

[119]. Type II tsRNAs are processed by different endonucleases. During processing of tRNA, the ribonucleases RNase P and RNase Z

remove the 5′ leader and 3′ trailer portions from the pre-tRNA sequence in the nucleus, respectively. Consequently, the released 3′

trailer sequence in the processing of tRNA becomes a type II tsRNA [114]. The biogenesis of tRNA halves (30–40 nt) initially found

in E. coli and was generated by PrrC nuclease in response to bacteriophage infection [120]. Later, this was reported in fungi and

mammals during various stress conditions, including amino acid or glucose starvation, heat shock, hypoxia, UV irradiation, or heavy

metal exposure [116]. In plants, tRNA halves are generated primarily by the activity of RNase T2 family enzymes, such as S-LIKE

RIBONUCLEASE 1 (RNS1), in response to various stress conditions [119].

Regulatory role of tRFs

The tRFs have various biological functions and participate in several cellular activities, most of which have been reported in

mammalian and yeast systems. In initial studies, the researchers found that the plant tRFs are associated with various stress

responses by quantifying the tRF levels. For instance, oxidative stress induces the accumulation of tRNA halves in plants. Thompson

et al. [121] found that, the abundance of tRNA halves from tRNATrpCCA, tRNAArgCCT and tRNAHisGTG peaked upon 4 h treatment with 5–10

mmol/L H2O2. Similarly, Cognat et al. [122] reported the higher amounts of tRF-5s from tRNAValAAC, tRNAGlyTCC, tRNAGlyGCC and

tRNAProTGG, accumulated in UV-stressed plants and also noticed that plastid tRF-5 populations fluctuated in drought, salinity and

cold conditions [122]. Various reports represent the roles of plant tRFs in phosphate (Pi)-limited conditions. The research by Hsieh

et al. [123] showed that 19 nt tRF-5s accumulated at higher levels in Pi-starved Arabidopsis roots. The probable reason is that Pi

deprivation could induce the level of RNS1 and an RNase T2, leading to the jumble of specific tRFs [119]. Above studies suggest that

tRFs can participate in numerous stress responses in plants.

The functional studies related to molecular mechanisms of plant tRFs are relatively limited, recent research supports that the plant tRFs regulate gene expression by mechanisms such as translation inhibition and RNA silencing. tRFs have been shown to participate in AGO-dependent gene silencing; for instance, in Arabidopsis, 19 nt tRFs were enriched in AGO1-IP sRNA populations, and the Long Terminal Repeat Gypsy retrotransposons are the major targets of tRFs [124]. Further, 19-nucleotide tRF-5 fragments have been demonstrated to cleave transposable element (TE) RNAs. This was supported by degradome/PARE sequencing and validated through an in vivo reporter assay, providing evidence for their role in targeting and slicing TE transcripts [124]. These results clearly suggest that plant tRFs regulate mobility of transposon by TE silencing. Ren et al. [125] recently reported that Bradyrhizobium japonicum (rhizobial symbiont) delivers tRFs to root cells of soybean (Glycine max). Further, the study highlighted that two rhizobium tRF-3s from tRNAVal and tRNAGly, and one tRF-5 from tRNAGln, are loaded into soybean AGO1, to cleave three essential genes responsible for root hair development in soybean by hijacking the host RNA silencing machinery. Thus, rhizobium-derived tRFs help in inducing the nodulation in soybean and participate in symbiotic interactions [125]. tRF also participate in plant pathogen interaction, for example, the 5′ tsR-Ala negatively regulates cytochrome P450 71A13(CYP71A13) expression and camalexin biosynthesis which repress the anti-fungal defense [126]. Further, they observed that upon fungal infection the expression of 5′tsR-Ala is downregulated as a plant defense strategy against fungal disease [126]. In Triticum aestivum, the expression of four out of nine wheat ribonuclease T2 family members is strongly induced by challenge with Fusarium graminearum. Further, the levels of three 5′-tRFs (tRFGlu-CUC, tRFLys-CUU, and tRFThr-CGU) are significantly higher in a Fusarium-susceptible than in a Fusarium-resistant cultivar, suggesting a potential role of these tRFs in Fusarium infections [127]. More recently, three specific tRFs (5′-tRFGln-UUG, 5′-tRFGln-CUG, and i-tRFGlu-UUC) were detected as highly abundant in the mycelium and other parts of the barley powdery mildew pathogen, Blumeria hordei. Their presence suggests a possible role in modulating host defense responses through cross-kingdom regulation [128].

Presently there are few reports on the role of plant tRFs in regulating translation. Studies have demonstrated that RNA molecules present in phloem sap can inhibit protein translation in vitro. It has also been reported that synthetic tRNA-derived fragments within the phloem sap may interfere with ribosomal function [129]. Similarly, using a green fluorescent protein reporter system in Arabidopsis, it was demonstrated that a subset of tRNA halves including other tRFs repress translation in vitro [130]. Combined together, the above evidences support the viewpoint that plant tRFs are engaged in several cellular activities, mainly in response to stress, transposon silencing and host-pathogen interactions by utilizing the translation inhibition mechanism and gene silencing.

Currently, NGS technologies have greatly hastened the quantitative analysis of tsRNAs. The sequencing methods, such as tRNA-seq [131], AQRNA-seq (absolute quantification RNA sequencing) [132] and 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate RNA sequencing (cP-RNA-seq) (133;134), are shown to sequence tRFs more efficiently, and databases such as tRFdb will help in the application of these identified tRFs in crop improvement. Thus, the identification of tRFs and their binding proteins are necessary to elucidate overall tRFs regulatory pathway and advance studies in this field is essential for uncovering the regulatory roles of these tRFs in plant cellular functions.

Conclusion and perspective

The regulatory landscape of ncRNAs in plants is vast and intricately complex, with these molecules functioning as key modulators of diverse cellular and developmental processes. The expression and biogenesis of ncRNAs are highly dynamic and strongly controlled, enabling plants to fine-tune the gene expression in response to developmental programs and ever-changing environmental stimuli. Upon perception of internal or external cues, specific ncRNAs are rapidly induced and orchestrate precise molecular interactions that regulate downstream pathways. This highlights the necessity of systematically identifying all regulatory factors, particularly ncRNAs, and deducing their functional significance for improving crop productivity, resilience, and quality.

Although notable progress has been achieved in elucidating the roles of small ncRNAs, particularly miRNAs and siRNAs, a large proportion of these molecules remain uncharacterized. Moreover, our understanding about ncRNA classes, such as lncRNAs, circRNAs, and ncRNA-derived fragments remains relatively limited. These unravelled categories of ncRNAs may hold crucial regulatory functions which are yet to be identified. High throughput sequencing technologies like NGS platform and integrative bioinformatics approaches now provide powerful tools to accelerate the identification, annotation, and functional characterization of ncRNAs. Meanwhile there is a need for development of robust, user-friendly databases that can curate and integrate the information on non-coding genetic elements to enhance the accessibility and utility for researchers worldwide. Altogether, these advances in technologies will aid in the discovery of novel ncRNAs and greatly improve the dissection of their mode of action in regulating major cellular processes. Ultimately, such knowledge will not only enhance our understanding about plant gene regulation but also provide innovative strategies for exploiting the information gained in crop improvement, enabling sustainable agricultural practices in current global challenges.

Acknowledgment

The authors sincerely acknowledge the Department of Plant Biotechnology, University of Agricultural Sciences, Bengaluru, for providing facility, resources and continuous support.

Draft Preparation- A.U.M, D.V., A.P.; Literature survey: V.S., A.P., D.V., A.U.M, Editing: A.P., D.V., V.S., Critical Reviews: D.V., A.U.M, V.S., Illustration: A.U.M, D.V.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jarroux J, Morillon A, Pinskaya M. History, Discovery, and Classification of lncRNAs. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1008:1-46. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5203-3_1.

- Bhatti GK, Khullar N, Sidhu IS, Navik US, Reddy AP, Reddy PH, Bhatti JS. Emerging role of non-coding RNA in health and disease. Metab Brain Dis. 2021;36(6):1119-1134. doi:10.1007/s11011-021-00739-y.

- Brosius J. Waste not, want not–transcript excess in multicellular eukaryotes. TRENDS in Genetics. 2005;21(5):287-288. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.02.014.

- Tants JN, Schlundt A. The role of structure in regulatory RNA elements. Biosci Rep. 2024;44(10):BSR20240139. https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20240139.

- Yadav A, Mathan J, Dubey AK, Singh A. The emerging role of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in plant growth, development, and stress response signalling. Non-coding RNA. 2024;10(1):13-37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna10010013.

- Beylerli O, Gareev I, Sufianov A, Ilyasova T, Guang Y. Long noncoding RNAs as promising biomarkers in cancer. Noncoding RNA Res. 2022;7(2):66-70. doi:10.1016/j.ncrna.2022.02.004.

- Zhang P, Wu W, Chen Q, Chen M. Non-Coding RNAs and their Integrated Networks. J IntegrBioinform. 2019;16(3):20190027. doi:10.1515/jib-2019-0027.

- Yoon JH, Kim J, Gorospe M. Long noncoding RNA turnover. Biochimie. 2015;117:15-21. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2015.03.001.

- Wang J, Mei J, Ren G. Plant microRNAs: Biogenesis, Homeostasis, and Degradation. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:360-372. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00360.

- Cobb M. Who discovered messenger RNA? Curr Biol. 2015;25:R526–R532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.032.

- Palade GE. A small particulate component of the cytoplasm. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1955;1(1):59–68. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.1.1.59.

- Kresge N, Simoni RD, Hill RL. The discovery of tRNA by Paul C. Zamecnik. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(40):e37–e39. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(20)79029-0.

- Inouye M, Delihast N. Small RNAs in the prokaryotes: a growing list of diverse roles. Cell. 1988;53:5-7. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(88)90480-1.

- Bartolomei MS, Zemel S, Tilghman SM. Parental imprinting of the mouse H19 gene. Nature. 1991;351:153–155. https://doi.org/10.1038/351153a0.

- Brown CJ, Ballabio A, Rupert JL, et al. A gene from the region of the human X inactivation centre is expressed exclusively from the inactive X chromosome. Nature. 1991;349:38–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/349038a0.

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75(5):843–854. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y.

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391(6669):806-11. doi:10.1038/35888.

- Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136(4):642-55. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035.

- Chinnusamy V, Zhu J, Zhou T, Zhu JK. Small RNAs: big role in abiotic stress tolerance of plants. In: Advances in molecular breeding toward drought and salt tolerant crops. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2007. p.223-260. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5578-2_10.

- Yu Y, Jia T, Chen X. The 'how' and 'where' of plant microRNAs. New Phytol. 2017;216(4):1002-1017. doi:10.1111/nph.14834.

- Yu B, Yang Z, Li J, Minakhina S, Yang M, Padgett RW, Steward R, Chen X. Methylation as a crucial step in plant microRNA biogenesis. Science. 2005;307(5711):932-935.

- Park MY, Wu G, Vaucheret H, Poethig RS. Nuclear processing and export of microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(10):3691-3696. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0405570102.

- Patil VS, Zhou R, Rana TM. Gene regulation by non-coding RNAs. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;49(1):16-32. doi:10.3109/10409238.2013.844092.

- Quintero A, Pérez-Quintero AL, López C. Identification of ta-siRNAs and cis-nat-siRNAs in cassava and their roles in response to cassava bacterial blight. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2013;11(3):172-81. doi:10.1016/j.gpb.2013.03.001.

- Brosnan CA, Voinnet O. Cell-to-cell and long-distance siRNA movement in plants: mechanisms and biological implications. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2011;14(5):580-7. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2011.07.011.

- Li Q, Wang Y, Sun Z, Li H, Liu H. The Biosynthesis Process of Small RNA and Its Pivotal Roles in Plant Development. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(14):7680. doi:10.3390/ijms25147680.

- Holoch D, Moazed D. RNA-mediated epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16(2):71-84. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3863.

- Mitter N, Dietzgen RG. Use of hairpin RNA constructs for engineering plant virus resistance. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;894:191-208. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-882-5_13.

- Singh K, Callahan AM, Smith BJ, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of RNAi-mediated virus resistance in ‘HoneySweet’ plum. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:726881. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.726881.

- AinQurat S, Elçi E. Knockdown of orthotospovirus-derived silencing suppressor gene by plant-mediated RNAi approach induces viral resistance in tomato. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2024;131:102264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmpp.2024.102264.

- Kheta RT, Anitha P, Deepika V. Intron hairpin RNA derived from the HC-Pro gene confers resistance to papaya ringspot virus in transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Sci Today. 2025. https://horizonepublishing.com/journals/index.php/PST/article/view/9312.

- Zhang J, Khan SA, Heckel DG, Bock R. Next-generation insect-resistant plants: RNAi-mediated crop protection. Trends Biotechnol. 2017;35(9):871-882. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.04.009.

- Hashmi MH, Tariq H, Saeed F, et al. Harnessing plant-mediated RNAi for effective management of Phthorimaea absoluta by targeting AChE1 and SEC23 genes. Plant Stress. 2024;14:100569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2024.100569.

- Christiaens O, Whyard S, Vélez AM, Smagghe G. Double-stranded RNA technology to control insect pests: current status and challenges. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:451. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00451.

- Srivastava S, Karuppannasamy A, Selvamani SB, et al. RNAi-mediated effective gene silencing of multiple targets in the Asia-I genetic group of Bemisia tabaci using dsRNA through oral delivery. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2025;19:103742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2025.103742.

- Reddy NV, et al. Apprehending siRNA machinery and gene silencing in brinjal shoot and fruit borer, Leucinodes orbonalis. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2025;118(1):e70029. https://doi.org/10.1002/arch.70029.

- Koch A, Biedenkopf D, Furch A, et al. An RNAi-based control of Fusarium graminearum infections through spraying of long dsRNAs involves a plant passage and is controlled by the fungal silencing machinery. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(10):e1005901. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1005901.

- Wang M, Dean RA. Host induced gene silencing of Magnaporthe oryzae by targeting pathogenicity and development genes to control rice blast disease. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:959641. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.959641.

- Jin W, Zhang X, Wu F, Zhang P. Selection of BcTRE1 as an effective RNAi target for dsRNA-based control of Botrytis cinerea. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2025;102773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmpp.2025.102773.

- Baysal Ö, Bastas KK. Host-Induced Gene Silencing: Approaches in Plant Disease Management. In: Microbial Biocontrol: Sustainable Agriculture and Phytopathogen Management. 2022. p.33-50.

- Andrade CM, Tinoco ML, Rieth AF, Maia FC, Aragão FJ. Host-induced gene silencing in the necrotrophic fungal pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Pathol. 2016;65(4):626-32.

- Zand-Karimi H, Innes RW. Molecular mechanisms underlying host-induced gene silencing. Plant Cell. 2022;34(9):3183-99.

- De-Schutter K, Taning CN, Van Daele L, et al. RNAi-based biocontrol products: Market status, regulatory aspects, and risk assessment. Front Insect Sci. 2022;1:818037.

- Qiao L, Niño-Sánchez J, Hamby R, et al. Artificial nanovesicles for dsRNA delivery in spray-induced gene silencing for crop protection. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023;21(4):854-65.

- Barciszewska-Pacak M, Milanowska K, Knop K, et al. Arabidopsis microRNA expression regulation in a wide range of abiotic stress responses. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:410. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00410.

- Fu R, Zhang M, Zhao Y, et al. Identification of salt tolerance-related microRNAs and their targets in maize (Zea mays L.) using high-throughput sequencing and degradome analysis. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:864. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00864.

- Hamza NB, Sharma N, Tripathi A, Sanan-Mishra N. MicroRNA expression profiles in response to drought stress in Sorghum bicolor. Gene Expr Patterns. 2016;20(2):88-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gep.2016.01.001.

- Wang M, Wang Q, Zhang B. Response of miRNAs and their targets to salt and drought stresses in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Gene. 2013;530(1):26-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2013.08.009.

- Xu S, Liu N, Mao W, Hu Q, Wang G, Gong Y. Identification of chilling-responsive microRNAs and their targets in vegetable soybean (Glycine max L.). Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):26619. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26619.

- Li D, Liu Z, Gao L, et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of microRNAs in developing grains of Zea mays L. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153168. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153168.

- Li B, Wang P, Zhao S, et al. Sly-miR398 participates in heat stress tolerance in tomato by modulating ROS accumulation and HSP response. Agronomy. 2025;15(2):294. doi:10.3390/agronomy15020294.

- Yang Z, Zhang L, Li J, et al. miR395 regulates sulfur metabolism and root development in Chinese kale under sulfur deficiency. Environ Exp Bot. 2025:106204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2025.106204.

- Chen X, Chen Z, Watts R, Luo H. Non-coding RNAs in plant stress responses: molecular insights and agricultural applications. Plant Biotechnol J. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.70134.

- Guan Y, Zhou L, Wang K, et al. Tae-miR156 negatively regulates wheat resistance to powdery mildew. S Afr J Bot. 2025;184:806–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2025.06.051.

- Li J, Song Q, Zuo ZF, Liu L. MicroRNA398: a master regulator of plant development and stress responses. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(18):10803. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231810803.

- Chiang CP, Li JL, Chiou TJ. Dose-dependent long-distance movement of microRNA399 duplex regulates phosphate homeostasis in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2023;240(2):802–814. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19182.

- Kotagama K, McJunkin K. Recent advances in understanding microRNA function and regulation in C. elegans. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2024;154:4-13. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2023.03.011.

- Smith NA, Corral M, Shu C, et al. Enhanced exogenous RNAi by loop-ended double-stranded RNA in plants. J Biotechnol. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2025.07.010.

- Knoblich M, et al. dsRNAs designed from functionally characterized siRNAs highly effective against Cucumber mosaic virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53(5):136. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaf136.

- NAAS. dsRNA-Biopesticides for Crop Protection. Policy Paper No. 139. National Academy of Agricultural Sciences, New Delhi; 2025. 14 pp.

- Schenkel W, Gathmann A. Regulatory aspects of RNAi in plant production. In: RNAi for Plant Improvement and Protection. CABI; 2021. p.154–158.

- Dietz-Pfeilstetter A, Mendelsohn M, Gathmann A, Klinkenbuß D. Considerations and regulatory approaches in the USA and in the EU for dsRNA-based externally applied pesticides for plant protection. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:682387.

- Amari K, Niehl A. Nucleic acid-mediated PAMP-triggered immunity in plants. Curr Opin Virol. 2020;42:32-9.

- Romeis J, Widmer F. Assessing the risks of topically applied dsRNA-based products to non-target arthropods. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:679.

- Parker KM, Barragán Borrero V, Van Leeuwen DM, et al. Environmental fate of RNA interference pesticides. Environ Sci Technol. 2019;53(6):3027-36.

- Qian X, Zhao J, Yeung PY, Zhang QC, Kwok CK. Revealing lncRNA structures and interactions by sequencing-based approaches. Trends Biochem Sci. 2019;44(1):33–52. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2018.09.012.

- Wang HV, Chekanova JA. Long Noncoding RNAs in Plants. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1008:133-154. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5203-3_5.

- Zafar J, Huang J, Xu X, Jin F. Recent Advances and Future Potential of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Insects. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):2605. doi:10.3390/ijms24032605.

- Heo JB, Sung S. Vernalization-mediated epigenetic silencing by a long intronic noncoding RNA. Science. 2011;331(6013):76–79. doi:10.1126/science.1197349.

- Ariel F, Jegu T, Latrasse D, et al. Noncoding transcription by alternative RNA polymerases dynamically regulates an auxin-driven chromatin loop. Mol Cell. 2014;55(3):383-396. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2014.06.011.

- Wang Y, Luo X, Sun F, et al. Overexpressing lncRNA LAIR increases grain yield and regulates neighbouring gene cluster expression in rice. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3516. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05829-7.

- Zhao X, Li J, Lian B, et al. Global identification of Arabidopsis lncRNAs reveals the regulation of MAF4 by a natural antisense RNA. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5056. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07500-7.

- Shin WJ, Nam AH, Kim JY, et al. Intronic long noncoding RNA, RICE FLOWERING ASSOCIATED (RIFLA), regulates OsMADS56-mediated flowering in rice. Plant Sci. 2022;320:111278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111278.

- Mammarella MF, Lucero L, Hussain N, et al. Long noncoding RNA-mediated epigenetic regulation of auxin-related genes controls shade avoidance syndrome in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2023;42(24):e113941. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2023113941.

- Seo JS, Sun HX, Park BS, et al. ELF18-INDUCED LONG-NONCODING RNA associates with mediator to enhance expression of innate immune response genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2017;29(5):1024-1038. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.16.00886.

- Kindgren P, Ard R, Ivanov M, Marquardt S. Transcriptional read-through of the long non-coding RNA SVALKA governs plant cold acclimation. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4561. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07010-6.

- Bardou F, Ariel F, Simpson CG, et al. Long noncoding RNA modulates alternative splicing regulators in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell. 2014;30(2):166-176. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2014.06.017.

- Zhang X, Wang W, Zhu W, et al. Mechanisms and Functions of Long Non-Coding RNAs at Multiple Regulatory Levels. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22):5573. doi:10.3390/ijms20225573.

- Franco-Zorrilla JM, Valli A, Todesco M, et al. Target mimicry provides a new mechanism for regulation of microRNA activity. Nat Genet. 2007;39(8):1033-1037. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng2079.

- Du Q, Wang K, Zou C, Xu C, Li WX. The PILNCR1-miR399 regulatory module is important for low phosphate tolerance in maize. Plant Physiol. 2018;177(4):1743-1753. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.18.00034.

- Tang Y, Qu Z, Lei J, et al. The long noncoding RNA FRILAIR regulates strawberry fruit ripening by functioning as a noncanonical target mimic. PLoS Genet. 2021;17(3):e1009461. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1009461.

- Meng J, Wang H, Chi R, et al. The eTM–miR858–MYB62-like module regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis under low-nitrogen conditions in Malus spectabilis. New Phytol. 2023;238(6):2524–2544. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18894.

- Liu X, Hao L, Li D, Zhu L, Hu S. Long non-coding RNAs and their biological roles in plants. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13(3):137-47. doi:10.1016/j.gpb.2015.02.003.

- Fonouni-Farde C, Ariel F, Crespi M. Plant Long Noncoding RNAs: New Players in the Field of Post-Transcriptional Regulations. Noncoding RNA. 2021;7(1):12. doi:10.3390/ncrna7010012.

- Guo A, Nie H, Li H, et al. The miR3367–lncRNA67–GhCYP724B module regulates male sterility. J Integr Plant Biol. 2025;67(1):169–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.13802.

- Jabnoune M, Secco D, Lecampion C, et al. A rice cis-natural antisense RNA acts as a translational enhancer. Plant Cell. 2013;25(10):4166-82. doi:10.1105/tpc.113.116251.

- Bazin J, Baerenfaller K, Gosai SJ, et al. Global analysis of ribosome-associated noncoding RNAs unveils new modes of translational regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(46):E10018-E10027. doi:10.1073/pnas.1708433114.

- Jin J, Lu P, Xu Y, et al. PLncDB V2.0: a comprehensive encyclopedia of plant long noncoding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D1489–D1495. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa910.

- Sanger HL, Klotz G, Riesner D, Gross HJ, Kleinschmidt AK. Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed circular RNA molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73(11):3852–3856. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.73.11.3852.

- Singh S, Sinha T, Panda AC. Regulation of microRNA by circular RNA. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2024;15(1):e1820. doi:10.1002/wrna.1820.

- Guria A, Sharma P, Natesan S, Pandi G. Circular RNAs—the road less traveled. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;6:146. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2019.00146.

- Xu S, Zhou L, Ponnusamy M, et al. A comprehensive review of circRNA: from purification and identification to disease marker potential. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5503. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5503.

- Wang Y, Yang M, Wei S, Qin F, Zhao H, Suo B. Identification of circular RNAs and their targets in leaves of Triticum aestivum L. under dehydration stress. Front Plant Sci. 2017;7:2024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.02024.

- Lasda E, Parker R. Circular RNAs: diversity of form and function. RNA. 2014;20(12):1829-42. http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.047126.114.

- Chen L, Huang C, Wang X, Shan G. Circular RNAs in eukaryotic cells. Curr Genomics. 2015;16(5):312–318. https://doi.org/10.1002/wrna.1820.

- Wilusz JE. Circular RNAs: unexpected outputs of many protein-coding genes. RNA Biol. 2017;14(8):1007-1017. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2016.1227905.

- Wang Y, Wang Z. Efficient backsplicing produces translatable circular mRNAs. RNA. 2015;21(2):172–179. http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.048272.114.

- Jeck WR, Sharpless NE. Detecting and characterizing circular RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(5):453–461. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2890.

- Panda AC, Grammatikakis I, Karreth F, eds. Structural and Functional Characterization of Circular RNAs. 2022.

- Zhou R, Sanz-Jimenez P, Zhu XT, et al. Analysis of rice transcriptome reveals the lncRNA/circRNA regulation in tissue development. Rice. 2021;14(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-021-00455-2.

- Cortés-López M, Miura P. Emerging functions of circular RNAs. Yale J Biol Med. 2016;89(4):527.

- Liu R, Ma Y, Guo T, Li G. Identification, biogenesis, function, and mechanism of action of circular RNAs in plants. Plant Commun. 2023;4(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xplc.2022.100430.

- Gao Z, Li J, Luo M, et al. Characterization and cloning of grape circular RNAs identified the cold resistance-related Vv-circATS1. Plant Physiol. 2019;180(2):966-985. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.18.01331.

- Sun X, Wang L, Ding J, et al. Integrative analysis reveals intuitive splicing mechanism for circular RNA. FEBS Lett. 2016;590(20):3510-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.12440.

- Wang Z, Liu Y, Li D, et al. Identification of circular RNAs in kiwifruit and response to bacterial canker pathogen invasion. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:413. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00413.

- Wang J, Yang Y, Jin L, et al. Re-analysis of lncRNAs and prediction of circRNAs reveal novel roles in susceptible tomato following TYLCV infection. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18(1):104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1332-3.

- Xiang L, Cai C, Cheng J, et al. Identification of circularRNAs and their targets in Gossypium under Verticillium wilt stress. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4500. doi:10.7717/peerj.4500.

- Ghorbani A, Izadpanah K, Peters JR, Dietzgen RG, Mitter N. Detection and profiling of circular RNAs in maize Iranian mosaic virus-infected maize. Plant Sci. 2018;274:402-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.06.016.

- Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, et al. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013;495(7441):384-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11993.

- Lu T, Cui L, Zhou Y, et al. Transcriptome-wide investigation of circular RNAs in rice. RNA. 2015;21(12):2076-87. http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.052282.115.

- Liu T, Zhang L, Chen G, Shi T. Identifying and characterizing the circular RNAs during the lifespan of Arabidopsis leaves. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1278. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01278.

- Conn VM, Hugouvieux V, Nayak A, et al. A circRNA from SEPALLATA3 regulates splicing of its cognate mRNA through R-loop formation. Nat Plants. 2017;3(5):53. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2017.53.

- Alves CS, Nogueira FT. Plant small RNA world growing bigger: tRNA-derived fragments. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:638911. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2021.638911.