Summary

Cancer continues to pose a significant global health challenge, prompting continuous research and innovation in therapeutic modalities. Among the evolving methods and approaches, therapies derived from peptides have emerged as an upcoming frontier, within the bounds of anticancer treatments. Peptides play a crucial role in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of hematologic malignancies. These short amino acid chains influence tumour growth, immune response, and cellular signaling in leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma. Therapeutic peptides, including peptide-based vaccines and receptor-specific targeted therapies such as those interfering with tumour-specific antigens or overexpressed surface proteins are emerging as promising treatment modalities. Over the last two decades, the advent of anticancer peptides (ACPs) has brought about transformative changes in the pharmaceutical landscape, offering novel avenues for combating malignancies. This comprehensive review analyzes the implementation of peptide-based treatments concerning blood malignancies, uncovering the mechanisms behind the effectiveness of anticancer peptides (ACPs), including interactions with negatively charged cellular surfaces, pore formation, and immune responses, it also states their targeted toxicity towards cancer cells. Additionally, peptide biomarkers aid in early diagnosis and disease monitoring. This review also emphasizes the role of peptides in pharmaceutical applications, investigating various drug delivery methods such as oral, nasal, ocular, and blood-brain barrier routes.

Keywords

Anticancer Peptides, Peptide Biomarkers and Peptide-based vaccines.

Introduction

Cancer being the second leading cause of death, stands as a formidable public health issue globally. As it is the leading cause of illness and death rates worldwide, it requires continuous research and exploration for the development of treatment methods and advancement in strategies [1]. It's crucial to address difficulties and obstacles in cancer treatment, such as the emergence of polydrug resistance and the restraint to neoplasm targeted treatments. Cancer is medically diagnosed as an uncontrolled and abnormal growth of cells within the living body, leading to their amplification and propagation to other tissues and organs. It can be classified into various types based on their characteristics, risk element and treatment methods and models. Usually, they are categories by the organ location or prevalence basis such as bladder cancer, breast cancer, colon cancer, kidney cancer, liver or lung cancer, melanoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma etc. For understanding, cancer is classified as solid cancer and non-solid cancer (cancers of the blood, such as leukemias) also called hematologic malignancies. Solid cancer is a neoplasm that doesn’t contain a liquid region or cyst. It can be cancerous (malignant) or non-cancerous (benign). Whereas nonsolid cancer such as leukemias is the result of production of large numbers of abnormal cells that enter the bloodstream. While significant steps have been taken in cancer treatments and therapy, there persists a critical demand for more potent and precisely targeted treatments to address the evolving dynamics of this complex disease [2]. One area of investigation is peptide derived treatments. Over the last two decades anticancer peptide, a group of tumours fighting agents have proven to transform and revolutionize the pharmaceutical field [3].

Hematologic malignancies

Hematologic malignancies, commonly known as blood cancers or non-solid tumours also abbreviated as (HMs), comprise a heterogeneous and

varied bracket of diseases marked by the unchecked proliferation of blood forming cells and lymphoid tissues. Hematologic malignancies

broadly categorized into myeloid and lymphatic tumours [4]. Both brackets responsible for disrupting the hematopoietic processes, i.e.

production and development of blood cells. Myeloid and lymphatic tumours can be distinguished on their origin in different

immune-system cells. Myeloid tumour or leukaemia are characterized by the presence of an abnormally high number of myeloid cells

throughout the bloodstream. Lymphocytic leukaemia or tumours also involve an overgrowth of lymphocytes, which can be found in

lymphatic tissues, the bloodstream, bone marrow, and other body tissues. They are further categorized into prevalent subtypes,

including leukaemia, multiple myeloma (MM), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) [4,5].

Among hematologic malignancies, Hodgkin lymphoma had the largest decline in the past few decades, with an age-standardized death rate (ASDR) of 0.34 per 100,000 population in 2019 [6]. Blood cancer comprises a substantial portion, approximately 6.5%, of global cancer cases. Currently, While the global incidence of leukemia is on the decline, certain developed regions like France, Spain, Slovenia, and Cyprus are witnessing a rise in cases. The prevalence of specific hematologic malignancies varies across countries and regions, influenced by distinct socioeconomic development stages [7]. Despite significant improvements in survival rates over recent decades, understanding the nuanced arrangements and temporal trends in illness and death rates related to hematologic malignancies remains imperative. This knowledge serves as a foundation for devising more targeted prevention strategies to further enhance the outcomes for individuals affected by these diverse malignancies [8].

Anticancer Peptides (ACPs): Mechanisms of Action

The anticancer peptides (ACPs) are sub-micron particles, usually consisting of fewer than 50 amino acids in terms of biological

molecules. It displays a cationic nature, characterized by the existence of basic and nonpolar residues [9]. Since peptides have

numerous advantages such as high specificity, minimal toxicity, effective tissue penetration, and versatility in modifications,

it is opted-for treatment and therapy when contrasted to antibodies and molecules [10]. Notably, ACPs often share key characteristics

with their predecessors, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) as they are derived from (AMPs), which results in overlapping features

between the two peptide classes [9, 11]. One fundamental feature of ACPs is their interaction with negatively charged cellular surfaces.

In both bacterial and cancer cells, the cell membranes bear a negative charge, making them susceptible targets for these peptides [12].

This electrostatic interaction is believed to determine the selective toxicity of ACPs against cancer cells, distinguishing them from

normal cells.Besides inhibition by heparan sulfates (e.g., against LfcinB and KW5), resistance to anticancer peptides can arise from:

Altered membrane lipid composition (less peptide binding) Protease-mediated degradation of peptides Efflux pump overexpression reducing

intracellular peptide levels Tumour microenvironment barriers (acidic pH, dense ECM, proteases) Immune neutralization by antibodies

[11, 13]. The cytotoxicity profiles of ACPs classify them into categories like, length: <20aa for short; >20aa for long, source

(natural versus synthetic); structure (random coil, β-sheet, and α-helical); charge (amphipathic, cationic), the mode of action

(non-lytic versus membrane-lytic) [14]. The preferential action of an anticancer peptides against cancer cells can be explained by

various factors:

Increased Negative Charges

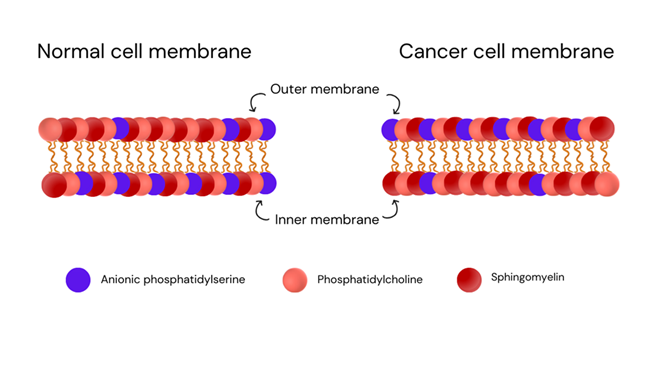

In normal cells, there's a structural arrangement in their membranes with asymmetric distribution. Anionic phosphatidylserine is

mainly situated on the inner side of the cell membrane. While the outer side is typically composed of neutral lipids like

phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin [15]. However, oncogenic cells disrupt the natural balance, as shown in Figure 1.

Factors like the acidic, low-oxygen environment, and elevated levels of reactive oxygen species in the tumour microenvironment (TME) cause phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine to shift from the inner to the outer leaflet of the membrane. This alteration results in a high concentration of anionic phosphatidylserine being exposed on the outer membrane of the cancer cell [16, 17]. These biochemical vulnerabilities make them targets for these peptides. Certain peptides, like NK-2, which originate from the central region of NK-lysin in pigs and T-cells, are effective against hematologic malignancies due to their positive charge. They work by selectively killing cancer cells through a process called necrosis. This ability is closely associated with the occurrence of phosphatidylserine (PS) on the surface of cancer cells. NK-2 can latch onto these molecules and disrupt the cancer cell's membrane, leading to its death [18]. The NK-2 peptide was found to be located alongside P-glycoprotein in cancer cells that are resistant to multiple drugs. This close association helped effectively target and eliminate these drug-resistant cells that had P-glycoprotein in the complex environment of tumours [19].

The environment around cancer cells is more acidic, with a pH shift from the normal 7.4 to 6.5 [20]. This acidic environment contributes to the development of the aggressive tumour characteristics seen in cancer [21] Furthermore, Cancer cells often have higher levels of certain negative molecules like sialic acid and glycosaminoglycans. These molecules make the surface of the cancer cells more negatively charged. Additionally, hyaluronan, another anionic glycosaminoglycan, further enhances the overall negative charge within tumour tissue [22, 23]. While it's generally true that the increased electrostatic negativity on the surface of oncogenic cells make them vulnerable to anticancer peptides, there's an interesting exception. Researchers discovered that when there is a lot of heparan sulfate on the outer leaflet of the cancer cell membrane, it can prevent anticancer peptides like LfcinB and KW5 from approaching the cell's inner membrane layer. As a result, this inhibits the peptides' ability to destroy the cancer cells. So, excessive heparan sulfate can act as a barrier and reduce their anticancer activity [24].

Pore formation

The ACP polybia-MPI, as well as bovine lactoferricin 6 (LfcinB6), have shown interesting properties in the context of cancer treatment

[25, 26] Polybia-MPI, a short α-helical peptide, exhibits selectivity towards leukemia cells, and this selectivity may be attributed

to variations in the level of exposed phosphatidylserine (PS) in the oncogenic cell membrane [26]

When tested for how well cells grow, survive, and respond to toxins, polybia-MPI was found to slow down the growth of both normal and drug-resistant cancer cells. At the same time, it increased the activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), which indicates cell damage [26]. However, its effect on normal fibroblast cells was much less.

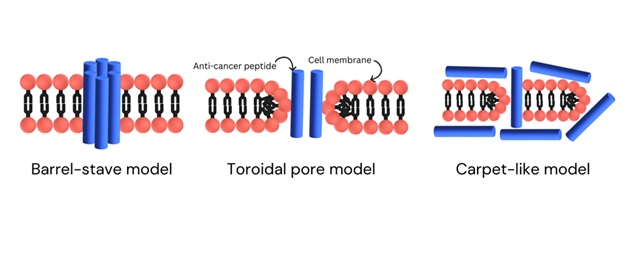

The biological membrane, the vital barrier defending the cell, is the first line of defense for a living cell. Pore forming proteins (PFP) play a key role in the host cell membrane alterations required to initiate the infection process. PFPs accomplish this process by changing from their soluble to membrane-bound forms. Because of this, these proteins frequently take on various structures and conformations, with one changing into the other during membrane interactions. The monomeric PFP subunit typically self-assembles into higher-order oligomeric species during this process, which are usually created in conjunction with a membrane scaffold. The development of effective drug molecules to treat a variety of infectious diseases has recently focused attention on membrane interactions and biological system activities by membrane proteins, such as the PFPs-lipid bilayer interactions [27]. Peptides typically orient themselves more perpendicular to the membrane as the concentration increases after initially binding parallel to the membrane at low concentrations. Additionally, insertion into the bilayer and the eventual formation of trans-membrane pores take place at high peptide/lipid ratios. Numerous models have been developed to explain the interactions between ACPs and cancer cell membranes. Numerous models have been developed to explain how ACPs interact with cancer cell membranes like the barrel-stave model, carpet model, toroidal or two-state model, detergent-like effect model or inverted micelle model and in-plane-diffusion model [28]

The mechanism of action of polybia-MPI relies on its ability to disrupt and alter the cell membrane by creating pores, which was confirmed through imaging studies, as mentioned in figure 2 [26]. In pore formation, the positively charged polybia-MPI are attracted to the anionic components on the outer layer of cancer cell membranes. This electrostatic attraction helps the peptide to attach to the cancer cell. Once attached to the cancer cell membrane, these polybia-MPI can embed themselves into the lipid bilayer. This insertion is often facilitated by hydrophobic associations between the peptide and the nonpolar regions of the lipid molecules in the membrane. As the peptide inserts into the membrane, it can cause alterations in the shape and structure of the lipid bilayer by adopting a helical conformation that is capable of breaching the membrane. This disruption leads to the formation of pores or blebbing (bulging), and even bursting of the cell. Consequently, hematologic malignant cells die through a necrotic process, characterized by cell swelling and eventual bursting [26].

The anticancer peptide (ACP) Polybia-MPI and bovine lactoferricin 6 (LfcinB6) primarily follow the barrel-stave model among the models, which are later addressed [29]. In the barrel-stave model, peptides accumulate and embed perpendicularly into the cell membrane, forming a structure similar to a barrel with the nonpolar regions of the peptides associating with the hydrophobic lipid tails of the plasma membrane [30]. This model results in the formation of transmembrane pores, which can grow larger as more peptides aggregate and the cell's contents start leaking out, resulting in cell lysis [25,26,29].

In contrast, the Toroidal Pore Model describes the anticancer peptides stick to the anionic regions i.e. the head part of the cell's membrane as they embed themselves into the membrane. As they keep entering, the membrane starts bending, forming a shape like a toroidal pore with a hole through it. This pore is made up of the membrane's head parts and the peptides inside it [31,32]. Because both positive and negative charges are present in this pore, it becomes stable. This process causes the cancer cell's membrane to lose its integrity, its charge, and leads to the leaking of the cell's contents, eventually lysis of cell [32, 33].

In the Carpet-Like Model the anticancer peptides with a positive charge act like carpets on the outer leaflet of cancer cell membrane. They are shaped like spirals and stick to the negatively charged part of the cell's outer layer. When enough of these peptides gather, they disrupt the order of the cell's outer layer, causing instability and making it break down. This disruption leads to the cell's membrane falling apart, ultimately causing the cancer cell to break open [29, 34].

Peptide structure:

SK84 is a glycine-rich peptide derived from a species of fruit fly called Drosophila virilis, and it possesses the remarkable ability

to disrupt the membranes of leukemia cells, as observed through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [35]. This disruption doesn't

happen because of electrostatic interactions seen with cationic peptides, as typically. SK84 seems to create membrane disruption

through an alternative mechanism. This mechanism involves the creation of an elastic structure within the membrane, likely associated

with the peptide’s flexible N-terminal regions, which are rich in glycine [35]. In simpler terms SK84 gently pushes and pulls the

membrane until it can't hold itself together anymore.

The peptide SK84 is quite selective. It's toxic to cancer cells but doesn't harm human red blood cells [35]. Leukaemia cells'

distinct lipid makeup or membrane elasticity may be the cause of SK84's selectivity, whereas RBCs are structurally more resistant to

mechanical disruption or do not have these weaknesses. This unique behavior makes SK84 a potential candidate for cancer treatment with

a different mode of action compared to other anticancer peptides.

Immune responses

LTX-302 is a 9-amino acid peptide with a positive charge, derived from bovine lactoferricin. When tested, it was found to shrink

tumours in models where A20 cell lymphomas were implanted under the skin. Injecting LTX-302 directly into tumours caused damage to

the cancer cell membranes, led to significant tumour death, and released tumour-associated antigens (TAAs). These tumour-associated

antigens (TAAs) were then picked up by dendritic cells and presented to T cells, starting an immune response. The effectiveness of

LTX-302 was shown in experiments with mice, where it not only had a local impact on the tumour but also triggered a strong and lasting

immune response against the cancer [36, 37].

Emerging ACPs

Magainins, initially isolated from the skin of Xenopus laevis, are a group of peptides renowned for their potent antibiotic properties

against diverse microorganisms. These peptides, typically made up of 21–27 amino acids and have a unique structure marked by positively

charged and hydrophobic regions [38]. The synthetic magainin peptide derivatives exhibit the ability to selectively target tumour cells,

inducing cytolytic activity. They show concentrations 5–10 times greater than what is required for antibacterial effects. This

selectivity extends to maintaining relatively low toxicity levels in normal cells. The underlying mechanism of action involves the

formation of α-helical channels on the membrane of tumour cells. This structural alteration impacts membrane permeability, leading to

a quick and permanent cell damage [39].

PEP2 and PEP3 are short and synthetic peptides made from the end part of the ARTS protein, which promotes cell death. These peptides demonstrated efficient cell-killing capabilities specifically targeting human leukemia cells. By harnessing the proapoptotic properties of ARTS, PEP2 and PEP3 offer a potential avenue for inducing programmed cell death in leukemia cells, a crucial aspect in cancer treatment [40]. Another innovative approach involves peptides known as BIM SAHBA. This peptide combines parts of the BIM protein, which helps trigger cell death, with a stable section of the BCL-2 protein. It targets the BCL-2 pathway, disrupting proteins that help cancer cells survive and activating proteins that lead to cell death. This approach helps overcome the resistance to cell death seen in blood cancers like leukemia. Tests in mice showed that BIM SAHBA can reduce the growth of leukemia tumours that are resistant to drugs. "BIM SAHBA helps leukaemia cells overcome resistance to apoptosis, especially those immune to BH3-mimetics and standard chemotherapies such as doxorubicin [41].

Anti-cancer peptide PNC-27 is a promising drug for clinical use. It interacts with a protein called hdm-2 on the cancer cell membrane, which causes pores to form and leads to cell death. It also disrupts the mitochondria inside the cancer cells. In PNC-27 treated cancer cells, the mitochondria lose the dye indicating healthy function, while the lysosomes retain their dye. Special imaging revealed that PNC-27 was located on the mitochondrial membranes.

Pharmaceutical Applications of peptides

Recent strides in biopharmaceutical engineering have led to the creation of numerous peptide-based drugs [42, 43, 44]. The number of

peptide drugs entering clinical trials has grown rapidly over the past 40 years. The market for peptide drugs, especially active

pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), has also expanded significantly. While peptide drugs used to be shorter, typically around 10

amino acids long, they are now often 30 to 40 amino acids long. Advances in technology have improved the ability to characterize

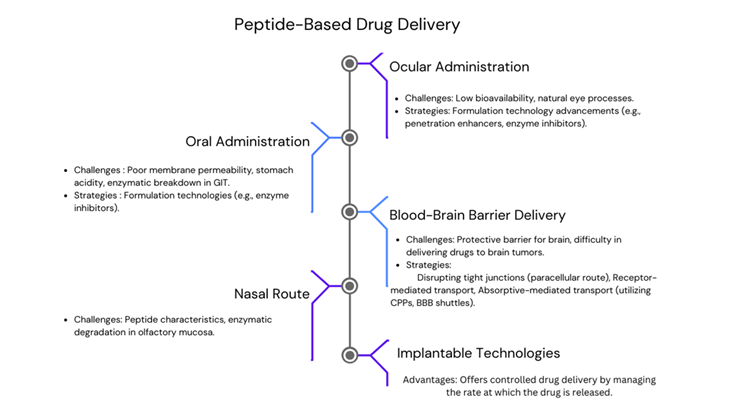

and manufacture these larger peptides in large quantities. The method through which a drug is administered significantly influences

its efficacy [45]. While the conventional needle-and-syringe approach is widely used, it presents issues with patient convenience,

expense, and maintaining sterility. This section explores different administration routes proposed for peptides, aiming to overcome

these limitations and enhance therapeutic outcomes, as shown in Figure 3. Peptides are typically delivered through invasive methods

like injections, but several non-invasive options have been investigated, such as nasal, buccal, transdermal, and pulmonary routes,

particularly for chronically administered drugs.

Oral drug administration is widely favoured for its convenience. But peptide drug molecules are generally not delivered orally. Due to poor membrane permeability, stomach acidity, and susceptibility to enzymatic breakdown in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), but such challenges could be overcome by exploring various formulation technologies, including co-administering enzyme inhibitors with therapeutic peptides to enhance absorption and bioavailability [46]. Administration of drugs through the eyes proves beneficial for treating ocular malignant tumours, albeit facing challenges related to natural eye processes. The bioavailability of peptides could lead to potential cost issues. Ongoing advancements in formulation technology are made for optimizing the efficacy by incorporating penetration enhancers and enzyme inhibitors [47].

The nasal route for peptide delivery works by using different ways to get the peptides through the nasal membrane, such as passive diffusion mechanisms, carrier-mediated transport, and transcytosis. It appeals as a pain-free and non-invasive administration route for peptide delivery. While this method has benefits like increased permeation and rapid absorption, challenges persist too. These include constrained dosage and enzyme degradation in the olfactory mucosa [46].

Researchers are exploring peptides that can specifically target tumours or blood vessels, aiming to improve drug delivery to brain cancers. One approach involves disrupting the tight junctions between endothelial cells that make up the BBB (blood-brain barrier), allowing drugs to pass through the spaces between these cells (paracellular route). Another strategy maintains the integrity of the BBB (blood-brain barrier) but delivers drugs through receptor-mediated transport. In this method, drugs are attached to peptides that mimic specific ligands. Additionally, drugs can be transported through absorptive-mediated transport, where cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) and BBB shuttles come into play [48, 49, 50]

Drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier primarily occurs through two routes: paracellular diffusion and the trans cellular route. Paracellular diffusion involves drugs moving between cells, but tight junctions normally prevent this process. To overcome this obstacle, researchers may disrupt or temporarily regulate the BBB. The transcellular route involves drugs passing through cells, traversing both the apical and basolateral membranes [50].

Light entering the eye, being focused by the cornea and lens onto the retina, and then being transformed into electrical signals by specialised cells are all examples of natural eye processes. The brain then decodes these signals as images after receiving them from the optic nerve. Recent advancements have also focused on implantable devices and technologies for delivering drugs via intracranial, intrathecal, or intravaginal routes, with notable progress in intraocular and subcutaneous implants. It offers controlled drug delivery by managing the rate at which the drug is released. Some of these technologies have received FDA approval. Ongoing research aims to enhance both implantable devices and in situ-forming implants, which may use nanomaterial formulations in non-bioabsorbable and biodegradable polymers [43].

Known Side effects of ACPs

Hemolysis (Red Blood Cell Damage)

Negatively charged membranes interact with a variety of cationic anticancer peptides. High dosages can also damage red blood cell

membranes, resulting in hemolysis, even though cancer cells have a higher negative charge than healthy mammalian cells [11]

Cytotoxicity to the normal cells

Off-target toxicity can result from certain ACPs' partial lack of selectivity and ability to harm non-cancerous mammalian cells [51]

Immunogenic complications

Peptides may trigger unintended immunological reactions, like hypersensitivity or the production of antibodies, which could lessen

the effectiveness of treatment or have negative consequences [52].

Rapid degradation and half-life

Serum proteases frequently break down peptides rapidly, necessitating high or frequent dosages that might cause systemic toxicity [13].

Potential for organ toxicity

Peptide buildup or metabolism, particularly at higher doses, has been linked to hepatic or renal stress in certain in vivo studies [14]

ACPs used in combinations

nation with chemotherapy:

Maganain II and Doxorubicin: By increasing doxorubicin uptake by membrane disruption, magainin II and doxorubicin demonstrated synergistic cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells [53].

Peptide & Cisplatin: Increases apoptosis in lung and ovarian cancer cells through cisplatin sensitization of tumour cells [54].

Combination with immunotherapy

LTS 315 (oncolytic peptide): releases tumour antigens, triggers immunogenic cell death, and has been used in conjunction with immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4) to increase T-cell-mediated tumour clearance [55].

Defensins (e.g., hBD-2, hBD-3): demonstrated to enhance checkpoint blockade and cancer vaccines by acting as chemoattractant for T cells and dendritic cells [56]

Combination with radiotherapy

LTS 315 + Radiation: improved local and systemic anticancer responses by increasing the immunogenicity of irradiation tumours, leading to improved tumour control in preclinical animals [55]

TP10 peptide (Transportan-10): encouraged glioblastoma cell apoptosis and DNA damage when paired with radiation [57].

Conclusion

In conclusion, cancer remains a formidable global public health issue, necessitating ongoing research and innovation in therapeutic approaches. The complex nature of cancer, with its diverse types and evolving challenges, demands potent and precisely targeted treatments. Peptide-based therapies, particularly Anticancer Peptides (ACPs) are promising for exploration over the last two decades, revolutionizing the pharmaceutical landscape. Hematologic malignancies, comprising a significant portion of global cancer cases, present a specific focus for ACP research. Notable ACPs, like NK-2 and Polybia-MPI, have demonstrated effectiveness against hematologic malignancies, showcasing the potential of these peptides in addressing blood cancers. Additionally, innovative ACPs like SK84, LTX-302, Magainins, Pep2, Pep3, BIM SAHBA, and PNC-27 exhibit diverse mechanisms of action, further expanding the repertoire of peptide-based anticancer strategies. Beyond their therapeutic potential, ACPs offer advantages in terms of minimal toxicity, effective tissue penetration, and versatility in modifications. The emerging discoveries of ACPs, especially those inducing immune responses, hold promise for developing comprehensive cancer treatment strategies. Moreover, the pharmaceutical applications of peptides extend to alternative drug delivery routes, addressing challenges associated with conventional methods. Oral, nasal, ocular, and blood-brain barrier routes provide avenues for optimizing drug administration, enhancing bioavailability, and improving patient convenience.

References

- Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S., & Jemal, A. (2023). Cancer statistics, 2023. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 73(1), 17–48.

- Marqus, S., Pirogova, E., & Piva, T. J. (2017). Evaluation of the use of therapeutic peptides for cancer treatment. Journal of Biomedical Science, 24, 1–15.

- Vlieghe, P., Lisowski, V., Martinez, J., & Khrestchatisky, M. (2010). Synthetic therapeutic peptides: science and market. Drug Discovery Today, 15(1–2), 40–56.

- Karagianni, P., Giannouli, S., & Voulgarelis, M. (2021). From the (Epi) genome to metabolism and vice versa; examples from hematologic malignancy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(12), 6321.

- Damlaj, M., El Fakih, R., & Hashmi, S. K. (2019a). Evolution of survivorship in lymphoma, myeloma and leukemia: metamorphosis of the field into long term follow-up care. Blood Reviews, 33, 63–73.

- Zhang, N., Wu, J., Wang, Q., Liang, Y., Li, X., Chen, G., Ma, L., Liu, X., & Zhou, F. (2023). Global burden of hematologic malignancies and evolution patterns over the past 30 years. Blood Cancer Journal, 13(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-023-00853-3.

- Hemminki, K., Hemminki, J., Försti, A., & Sud, A. (2022). Survival trends in hematological malignancies in the Nordic countries through 50 years. Blood Cancer Journal, 12(11), 150.

- Damlaj, M., El Fakih, R., & Hashmi, S. K. (2019b). Evolution of survivorship in lymphoma, myeloma and leukemia: Metamorphosis of the field into long term follow-up care. Blood Reviews, 33, 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BLRE.2018.07.003.

- Tyagi, A., Tuknait, A., Anand, P., Gupta, S., Sharma, M., Mathur, D., Joshi, A., Singh, S., Gautam, A., & Raghava, G. P. S. (2015a). CancerPPD: a database of anticancer peptides and proteins. Nucleic Acids Research, 43(D1), D837–D843.

- Otvos, L. (2008). Peptide-based drug design: here and now. Peptide-Based Drug Design, 1–8.

- Gaspar, D., Salomé Veiga, A., & Castanho, M. A. R. B. (2013). From antimicrobial to anticancer peptides. A review. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4 (OCT). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00294.

- Mader, J. S., & Hoskin, D. W. (2006). Cationic antimicrobial peptides as novel cytotoxic agents for cancer treatment. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs, 15(8), 933–946.

- Fosgerau, K., & Hoffmann, T. (2015). Peptide therapeutics: current status and future directions. Drug Discovery Today, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/development.

- Schweizer, F. (2009). Cationic amphiphilic peptides with cancer-selective toxicity. European Journal of Pharmacology, 625(1–3), 190–194.

- Yamaji-Hasegawa, A., & Tsujimoto, M. (2006). Asymmetric distribution of phospholipids in biomembranes. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 29(8), 1547–1553.

- Ran, S., Downes, A., & Thorpe, P. E. (2002). Increased exposure of anionic phospholipids on the surface of tumor blood vessels. Cancer Research, 62(21), 6132–6140.

- Zweytick, D., Riedl, S., Rinner, B., Asslaber, M., Schaider, H., Walzer, S., Novak, A., & Lohner, K. (2011). In search of new targets—the membrane lipid phosphatidylserine—the underestimated Achilles’ Heel of cancer cells. Annals of Oncology, 22, 43.

- Schröder-Borm, H., Bakalova, R., & Andrä, J. (2005). The NK-lysin derived peptide NK-2 preferentially kills cancer cells with increased surface levels of negatively charged phosphatidylserine. FEBS Letters, 579(27), 6128–6134.

- Banković, J., Andrä, J., Todorović, N., Podolski-Renić, A., Milošević, Z., Miljković, Đ., Krause, J., Ruždijić, S., Tanić, N., & Pešić, M. (2013). The elimination of P-glycoprotein over-expressing cancer cells by antimicrobial cationic peptide NK-2: the unique way of multi-drug resistance modulation. Experimental Cell Research, 319(7), 1013–1027.

- Logozzi, M., Spugnini, E., Mizzoni, D., Di Raimo, R., & Fais, S. (2019). Extracellular acidity and increased exosome release as key phenotypes of malignant tumors. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews, 38, 93–101.

- Cardone, R. A., Casavola, V., & Reshkin, S. J. (2005). The role of disturbed pH dynamics and the Na+/H+ exchanger in metastasis. Nature Reviews Cancer, 5(10), 786–795.

- Hąc-Wydro, K., Wydro, P., Cetnar, A., & Włodarczyk, G. (2015). Phospatidylserine or ganglioside–Which of anionic lipids determines the effect of cationic dextran on lipid membrane? Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 126, 204–209.

- Itano, N., & Kimata, K. (2009). Altered hyaluronan biosynthesis in cancer progression. Hyaluronan in Cancer Biology, 171–185.

- Fadnes, B., Rekdal, Ø., & Uhlin-Hansen, L. (2009). The anticancer activity of lytic peptides is inhibited by heparan sulfate on the surface of the tumor cells. BMC Cancer, 9, 1–13.

- Richardson, A., de Antueno, R., Duncan, R., & Hoskin, D. W. (2009). Intracellular delivery of bovine lactoferricin’s antimicrobial core (RRWQWR) kills T-leukemia cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 388(4), 736–741.

- Wang, K., Yan, J., Zhang, B., Song, J., Jia, P., & Wang, R. (2009). Novel mode of action of polybia-MPI, a novel antimicrobial peptide, in multi-drug-resistant leukemic cells. Cancer Letters, 278(1), 65–72.

- Sannigrahi, A., & Chattopadhyay, K. (2022). Pore formation by pore forming membrane proteins towards infections. Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology, 128, 79–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/BS.APCSB.2021.09.001.

- Oelkrug, C., Hartke, M., & Schubert, A. (2015). Mode of action of anticancer peptides (ACPs) from amphibian origin. Anticancer Research, 35(2), 635–643.

- Dennison, S. R., Whittaker, M., Harris, F., & Phoenix, D. A. (2006). Anticancer α-helical peptides and structure/function relationships underpinning their interactions with tumour cell membranes. Current Protein and Peptide Science, 7(6), 487–499.

- Tornesello, A. L., Borrelli, A., Buonaguro, L., Buonaguro, F. M., & Tornesello, M. L. (2020). Antimicrobial peptides as anticancer agents: functional properties and biological activities. Molecules, 25(12), 2850.

- Lin, L., Chi, J., Yan, Y., Luo, R., Feng, X., Zheng, Y., Xian, D., Li, X., Quan, G., & Liu, D. (2021). Membrane-disruptive peptides/peptidomimetics-based therapeutics: Promising systems to combat bacteria and cancer in the drug-resistant era. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B, 11(9), 2609–2644.

- Sengupta, D., Leontiadou, H., Mark, A. E., & Marrink, S.-J. (2008). Toroidal pores formed by antimicrobial peptides show significant disorder. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes, 1778(10), 2308–2317.

- Brogden, K. A. (2005). Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nature Reviews Microbiology, 3(3), 238–250.

- Luan, X., Wu, Y., Shen, Y.-W., Zhang, H., Zhou, Y.-D., Chen, H.-Z., Nagle, D. G., & Zhang, W.-D. (2021). Cytotoxic and antitumor peptides as novel chemotherapeutics. Natural Product Reports, 38(1), 7–17.

- Lu, J., & Chen, Z. (2010). Isolation, characterization and anti-cancer activity of SK84, a novel glycine-rich antimicrobial peptide from Drosophila virilis. Peptides, 31(1), 44–50.

- Berge, G., Eliassen, L. T., Camilio, K. A., Bartnes, K., Sveinbjørnsson, B., & Rekdal, Ø. (2010). Therapeutic vaccination against a murine lymphoma by intratumoral injection of a cationic anticancer peptide. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy, 59, 1285–1294.

- Eksteen, J. J., Ausbacher, D., Simon-Santamaria, J., Stiberg, T., Cavalcanti-Jacobsen, C., Wushur, I., Svendsen, J. S., & Rekdal, Ø. (2017). Iterative design and in vivo evaluation of an oncolytic antilymphoma peptide. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 60(1), 146–156.

- Zasloff, M. (1987). Magainins, a class of antimicrobial peptides from Xenopus skin: isolation, characterization of two active forms, and partial cDNA sequence of a precursor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 84(15), 5449–5453.

- Cruciani, R. A., Barker, J. L., Zasloff, M., Chen, H.-C., & Colamonici, O. (1991). Antibiotic magainins exert cytolytic activity against transformed cell lines through channel formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 88(9), 3792–3796.

- Edison, N., Reingewertz, T.-H., Gottfried, Y., Lev, T., Zuri, D., Maniv, I., Carp, M.-J., Shalev, G., Friedler, A., & Larisch, S. (2012). Peptides mimicking the unique ARTS-XIAP binding site promote apoptotic cell death in cultured cancer cells. Clinical Cancer Research, 18(9), 2569–2578.

- LaBelle, J. L., Katz, S. G., Bird, G. H., Gavathiotis, E., Stewart, M. L., Lawrence, C., Fisher, J. K., Godes, M., Pitter, K., & Kung, A. L. (2012). A stapled BIM peptide overcomes apoptotic resistance in hematologic cancers. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 122(6), 2018–2031.

- Bottens, R. A., & Yamada, T. (2022). Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) as therapeutic and diagnostic agents for cancer. Cancers, 14(22), 5546.

- Cesaro, A., Lin, S., Pardi, N., & de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2023). Advanced delivery systems for peptide antibiotics. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 196, 114733.

- Merola, E., & Grana, C. M. (2023). Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT): innovations and improvements. Cancers, 15(11), 2975.

- Benet, L. Z. (1978). Effect of route of administration and distribution on drug action. Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Biopharmaceutics, 6, 559–585.

- Alabsi, W., Eedara, B. B., Encinas-Basurto, D., Polt, R., & Mansour, H. M. (2022). Nose-to-brain delivery of therapeutic peptides as nasal aerosols. Pharmaceutics, 14(9), 1870.

- Lee, V. H. L., Urrea, P. T., Smith, Ro. E., & Schanzlin, D. J. (1985). Ocular drug bioavailability from topically applied liposomes. Survey of Ophthalmology, 29(5), 335–348.

- Arvanitis, C. D., Ferraro, G. B., & Jain, R. K. (2020). The blood–brain barrier and blood–tumour barrier in brain tumours and metastases. Nature Reviews Cancer, 20(1), 26–41.

- Klimpel, A., Luetzenburg, T., & Neundorf, I. (2019). Recent advances of anti-cancer therapies including the use of cell-penetrating peptides. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 47, 8–13.

- Wettschureck, N., Strilic, B., & Offermanns, S. (2019). Passing the vascular barrier: endothelial signaling processes controlling extravasation. Physiological Reviews, 99(3), 1467–1525.

- Tyagi, A., Tuknait, A., Anand, P., Gupta, S., Sharma, M., Mathur, D., Joshi, A., Singh, S., Gautam, A., & Raghava, G. P. S. (2015b). CancerPPD: A database of anticancer peptides and proteins. Nucleic Acids Research, 43(D1), D837–D843.

- Felício, M. R., Silva, O. N., Gonçalves, S., Santos, N. C., & Franco, O. L. (2017). Peptides with dual antimicrobial and anticancer activities. Frontiers in Chemistry, 5 (Feb). https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2017.00005.

- Zhou, H., Forveille, S., Sauvat, A., Yamazaki, T., Senovilla, L., Ma, Y., Liu, P., Yang, H., Bezu, L., Müller, K., Zitvogel, L., Rekdal, Ø., Kepp, O., & Kroemer, G. (2016). The oncolytic peptide LTX-315 triggers immunogenic cell death. Cell Death and Disease, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2016.47.

- Ren, S. X., Cheng, A. S. L., To, K. F., Tong, J. H. M., Li, M. S., Shen, J., Wong, C. C. M., Zhang, L., Chan, R. L. Y., & Wang, X. J. (2012). Host immune defense peptide LL-37 activates caspase-independent apoptosis and suppresses colon cancer. Cancer Research, 72(24), 6512–6523.

- Sveinbjornsson, B., Camilio, K. A., Wang, M.-Y., Nestvold, J., & Rekdal, O. (2017). LTX-315: A first-in-class oncolytic peptide that reshapes the tumor microenvironment. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer, 5.

- Hilchie, A. L., Wuerth, K., & Hancock, R. E. W. (2013). Immune modulation by multifaceted cationic host defense (antimicrobial) peptides. Nature Chemical Biology, 9(12), 761–768.

- Myrberg, H., Zhang, L., Mäe, M., & Langel, Ü. (2008). Design of a tumor-homing cell-penetrating peptide. Bioconjugate Chemistry, 19(1), 70–75.