Summary

Paracoccus denitrificans is a metabolically adaptable prokaryote equipped with diverse oxidoreductase enzymes that enable persistence across soil, marine, and industrial environments. This study reviews key reductase enzyme families, including flavin, iron, quinone, and chromate/chromate-related reductases, emphasizing their biochemical roles and biotechnological potential. Flavin reductases catalyze coupled electron transfer, reducing both NAD(P)H to its active nicotinamide form and FAD to FADH₂. These reactions support essential pathways such as DNA biosynthesis, quinone detoxification, and light-associated microbial functions including bioluminescence. Iron reductases convert ferric iron (Fe³⁺) into bioavailable ferrous iron (Fe²⁺), a process critical for iron acquisition in nutrient-restricted habitats, where iron bioavailability dictates microbial competition and survival. Quinone reductases further strengthen stress tolerance by performing two-electron reductions that suppress harmful redox cycling, thereby preventing excess reactive oxygen species formation and improving oxidative stress resistance. Chromate reductases reduce toxic Cr(VI) to the stable, less soluble Cr(III) state, offering promising applications for chromium detoxification and water bioremediation. The broad substrate range and structural diversity of these enzymes highlight the unique capacity of microbial metabolism to sustain elemental cycling and chemical transformations distinct from higher organisms. Understanding these oxidoreductases advances microbial biochemistry while guiding innovative strategies in bioremediation, industrial biocatalysis, and environmental biotechnology.

Keywords

Electron transfer enzymes; Redox metabolism; Flavoenzymes; Environmental detoxification; Cofactor interaction.

Introduction

Microorganisms can inhabit a wide range of environments due to their remarkable metabolic capabilities [1]. Paracoccus denitrificans is a free-living coccoid bacterium commonly found in soil and water [2]. It is highly metabolically versatile and has long served as a model organism for studying diverse biochemical pathways [2]. P. denitrificans contains various enzymes and proteins, including several belongings to the flavoenzyme superfamily with NAD(P)H:FMN oxidoreductase activity. Until recently, FerA and FerB were the only well-characterized members of this group [3].

FerA and FerB are flavoenzymes with distinct physiological roles. FerA functions primarily as an iron and flavin reductase, enabling the bacterium to extract iron from extracellular sources—an essential adaptation for survival in iron-limited environments [4]. FerB, a quinone reductase, contributes to the detoxification of reactive species such as quinones and plays a protective role against oxidative stress. Together, these enzymes highlight the diverse strategies P. denitrificans employs to adapt to environmental pressures [5–7].

Flavin reductases constitute a major class of oxidoreductases that use NAD(P)H to reduce FMN and FAD cofactors [7]. These enzymes are essential for maintaining intracellular redox balance and participate in processes such as hydroxylation reactions, detoxification, and DNA synthesis [8]. They are classified into two types based on their flavin-binding properties, and their ability to act on substrates with varied structures reflects their versatility and significance in microbial metabolism [9].

Iron reductases are key enzymes involved in microbial iron metabolism, reducing ferric iron (Fe³⁺) to its more bioavailable ferrous form (Fe²⁺) [10]. This reduction is crucial in siderophore-mediated iron uptake, particularly under iron-limiting conditions. These enzymes also contribute to metal detoxification and redox homeostasis. FRE1 and FRE2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae perform similar functions, demonstrating the evolutionary conservation of iron reductase activity across species. P. denitrificans and other relatives also possess quinone and chromate reductases that contribute to the environmental detoxification and xenobiotic degradation. While quinone reductases are related to protecting cells from oxidative damage by minimizing redox cycling of quinones, chromate reductase is involved in the process of converting toxic Cr(VI) to its nontoxic form Cr(III). These enzymes are structurally related to and may have the same substrate specificity as flavin reductases. The metabolic versatility of Paracoccus denitrificans is driven by oxidoreductase enzymes that mediate essential redox transformations, such as:

- NAD(P)H + FAD → NAD(P)+ + FADH₂

- Fe³⁺ + e⁻ → Fe²⁺

- Quinone + 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → Hydroquinone.

Such reactions demonstrate the organism’s ability to maintain redox balance, acquire important nutrients, and detoxify harmful compounds

Flavin Reductases

Flavin reductases are oxidoreductase enzymes (EC 1.5.1.x) that helps in catalysing the reduction of flavin cofactors, specifically

flavin mononucleotide (FMN) or flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), to their reduced forms FMNH₂ or FADH₂ [15]. The reducing equivalents

come from either NADH or NADPH, which are nicotinamide cofactors [16].

Flavin (oxidized) + NAD(P)H + H+ → Flavin (reduced) + NAD(P)+ [16]

The products, FMNH₂ or FADH₂, act as electron donors for various downstream biochemical processes, they play key roles in maintaining cellular redox balance and in allowing oxidative biochemical changes [17][18].

Class I Flavin Reductases

The active site of these enzymes contains flavin cofactors that are tightly bound, sometimes covalently bound [19]. They usually act

according to a ping-pong (double displacement) mechanism, in which the flavin cofactor is reduced after accepting electrons from

NAD(P)H [19][23]. Electrons are then transferred to an external electron acceptor by the reduced flavin. In a case study of

Escherichia coli’s Fre (flavin reductase), which catalyses the reduction of substrates and has a tightly bound FMN [20]. In Class

I enzymes, the tight binding of flavin allows for rapid cycling between oxidized and reduced forms, enabling high turnover rates [21].

Class II Flavin Reductases

These enzymes do not have bound flavin in their active site. Rather, they reduce free flavin molecules (FMN or FAD) present in the

medium [22]. They work by sequential kinetic mechanism in which a ternary complex (enzyme–NAD(P)H–flavin) develops rapidly during

catalysis. Vibrio fischeri’s NADPH-flavin reductase converts free FMN to FMNH₂ for the bacterial luciferase reaction [22]. Class II

flavin reductases are necessary in pathways where reduced flavin is required as a diffusible intermediate for other enzymes [23]. They

are small to medium-sized proteins (~20–35 kDa), some multi-domain enzymes are larger.[24]. Many flavin reductases share a Rossmann

fold for binding NAD(P)H [25]. Some of them prefer NADPH, while others accept both NADH and NADPH [26]. Many flavin reductases can be

identified by their substrate promiscuity, which allows them to reduce several electron acceptors apart from flavins, including [12]:

Quinones: Flavin reductases convert quinones to hydroquinone, reducing oxidative stress by inhibiting redox cycling and ROS production

[27]. Nitroaromatic compounds: Fre in E. coli can reduce nitroaromatic contaminants such as nitrobenzene, contributing to

detoxification processes [10] (table 1). Azo dyes: Flavin reductases reduce azo bonds (–N=N–) to decolorize dye, which is relevant

in bioremediation [11]. Chromate (Cr(VI)): Bacterial flavin reductases can reduce chromate Cr(VI) to less harmful Cr(III), potentially

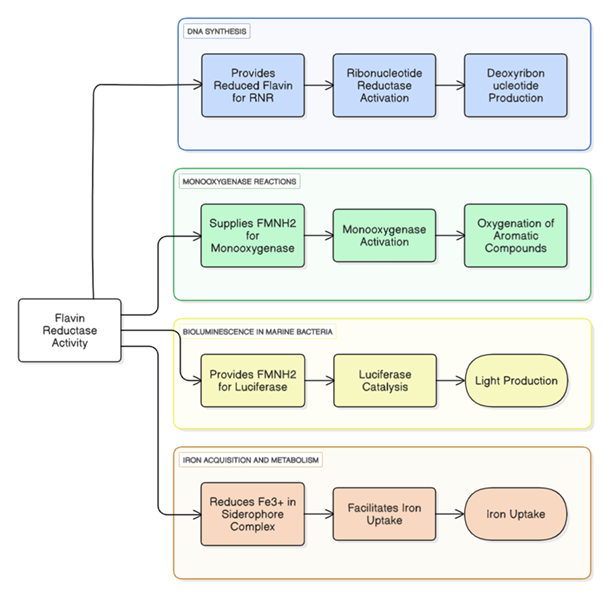

contributing to environmental maintenance [9]. (Physiological functions of Flavin reductase is illustrated in Figure 1).

Physiological Functions Iron Reductases

Flavin reductase activity is involved in several important cellular processes: DNA synthesis – Provides reduced flavins essential for

ribonucleotide reductase, enabling deoxyribonucleotide production crucial for DNA replication [28]. Monooxygenase reactions – Supplies

FMNH₂ for monooxygenases, facilitating the oxygenation of aromatic and xenobiotic compounds [29]. Bioluminescence in marine bacteria –

Generates FMNH₂ for bacterial luciferase, supporting light production for communication and survival [30]. Iron acquisition and

metabolism – Reduces Fe³⁺ in siderophore complexes, enhancing iron uptake under limiting conditions [31], (The mechanism is

illustrated in Figure 1).

Iron Reductases

Iron reductases are a class of oxidoreductase enzymes that catalyze the conversion of ferric iron (Fe³⁺) to its bioavailable ferrous

form (Fe²⁺) [36]. This reduction represents a critical step for microorganisms, plants, and some animal systems to acquire and utilize

iron efficiently under iron-limited conditions [36].

Fe3+ + e− → Fe2+ [36]

Fe³⁺ is poorly soluble and can’t be used by cell under normal conditions, hence it needs to be converted to Fe²⁺ is necessary for adsorption and intracellular utilization [37][38]. Integral membrane proteins play important role in transmembrane electron transfer. Example: FRE family in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [39]. Soluble (cytoplasmic or extracellular) iron reductases are located in the cytosol, periplasm, or released into the extracellular medium [36]. Help in reduction of Fe³⁺ outside the plasma membrane. Many iron reductases use flavin cofactors such as FMN or FAD as electron carriers [40]. In these enzymes, flavins mediate electron transfer from NAD(P)H or reduced cytochromes to Fe³⁺, promoting its reduction [41][42]. Molecular weight is ~20–40 kDa to >100 kDa for soluble enzymes for membrane-bound complexes [42][43]. Active site contains redox cofactors such as flavins, iron-sulfur clusters, or heme groups [41][44]. Many exhibits high affinity for Fe³⁺, crucial under iron-limited conditions [44][45].

Flavin reductases generate reduced flavins (FMNH₂/FADH₂) that support multiple cellular processes. These include activation of ribonucleotide reductase for DNA synthesis, provision of FMNH₂ to monooxygenases for substrate oxygenation, fueling luciferase-driven bioluminescence, and reduction of Fe³⁺ in siderophore complexes to facilitate iron uptake. (Source: Authors’ own work)

| Enzyme | Organism | Cofactor | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fre | E. coli | FMN-bound | Reduction of quinones and nitroaromaticsa,b |

| LuxG (flavin reductase) | Vibrio fischeri | FMN (free) | Generates FMNH₂ for bioluminescencec |

| ChrR | Pseudomonas putida | FMN-bound | Cr(VI) reductiond |

| NfsA/B | E. coli | FMN-bound | Nitroaromatic reductiona |

Mechanism of Action

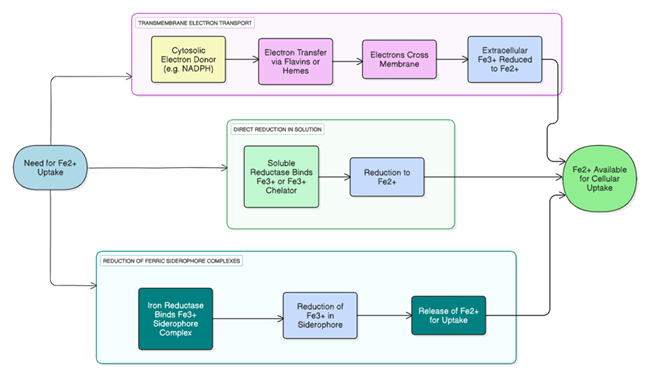

Cells require Fe²⁺ for uptake. They obtain it by reducing extracellular Fe³⁺ through three main pathways: Transmembrane Electron

Transport: Electrons from cytosolic donors like NADPH are transferred across the membrane, reducing Fe³⁺ outside the cell [40].

Direct Reduction in Solution: Soluble reductases bind Fe³⁺ (or Fe³⁺ chelators) and convert it to Fe²⁺ [40]. Reduction of Ferric

Siderophore Complexes: Iron reductases reduce Fe³⁺ bound in siderophores, releasing Fe²⁺ for uptake. All pathways ensure Fe²⁺ is

available for cellular needs [50]. (The mechanism of Flavin reductase is illustrated in Figure 2)

Quinone reductases are a subgroup of oxidoreductase enzymes that catalyse the reduction of quinones to hydroquinone [53][54]. This reaction is biologically crucial because it prevents quinones from engaging in redox cycling, a process that generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) and contributes to oxidative stress and cellular damage [55]. The general reaction catalysed by quinone reductases can be represented as:

These enzymes are often NADH- or NADPH-dependent and frequently contain flavin cofactors, particularly FMN or FAD, which mediate electron transfer during catalysis [56]. Quinone reductases are widely distributed across bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals, underscoring their conserved and essential protective roles in diverse biological systems [56].

Structural and Biochemical Features

Quinone reductases tend to be relatively small, with molecular weights of around 20-40 kDa [57]. Most multimeric complexes, such

as dimers or tetramers, are formed from these proteins [57]. These enzymes often carry out two-electron reductions. This strategy

not only avoids producing semiquinone radicals but also minimizes the generation of reactive oxygen species ('ROS') fcc and so

helps to protect cells [58]. This two-electron reduction stands in stark contrast with one-electron pathways. The latter could

easily produce short-lived intermediate radical semi-quinone prone to undergo harmful redox cycling processes [58].

Physiological Roles of Quinone Reductases

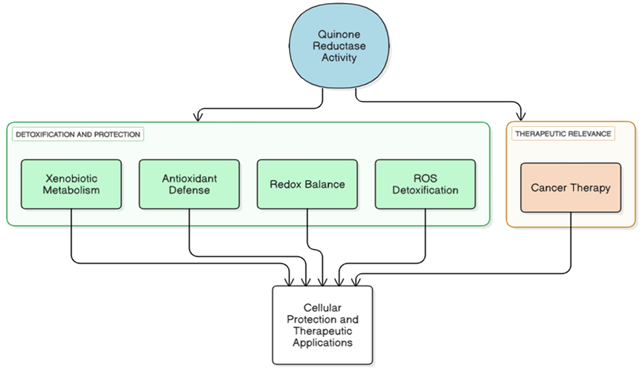

Roles of Quinone Reductase Activity in Cellular Protection and Therapy Quinone reductase activity contributes to detoxification and

protection through xenobiotic metabolism, antioxidant defense, redox balance, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification [58][59].

These functions support cellular protection and have therapeutic relevance, particularly in cancer therapy [60]. (Physiological

functions of Quinone reductase is illustrated in Figure 3).

Chromate Reductases Discussion

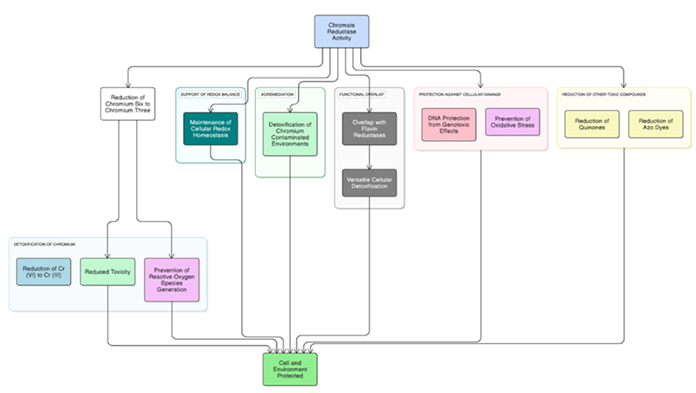

Chromate [Cr(VI)] is a toxic and mutagenic environmental contaminant [65]. Chromate reductases play a crucial role in reducing Cr(VI)

to Cr(III), a much less toxic and insoluble form, using NAD(P)H as an electron donor [66]. These enzymes are also attracting interest

for their potential application in bioremediation [67]. Many have the same structure as flavin reductases, and the same dependency

on cofactors [68]. Some of the best-characterized chromate reductases are: ChrR from Pseudomonas putida [69], NAD(P)H:quinone

reductase (NQR) from Arabidopsis thaliana, which exhibits action against chromium [70]. These enzymes usually act on a broad spectrum

of non-polar substrates. Cr(VI) reduction alleviates its toxic effects and precludes damage to DNA by stopping ROS formation [71].

The homology between these enzymes and FerC paralogs indicates that FerC might also have chromate reductase-like activity [72].

The figure illustrates three mechanistic routes for converting Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺: transmembrane electron transfer from cytosolic donors to extracellular Fe³⁺, direct reduction of soluble Fe³⁺ or Fe³⁺–chelator complexes, and reduction of ferric siderophore complexes. All pathways converge on generating Fe²⁺ in a form accessible for cellular uptake. (Source: Authors’ own work)

| Enzyme | Organism | Location | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| FRE1 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Plasma membrane | Reduces extracellular Fe³⁺ for uptakea |

| FRE2 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Plasma membrane | Similar function as FRE1, with broader substrate rangea |

| Ferric reductase | Escherichia coli | Periplasmic/cytoplasmic | Reduction of ferric-siderophore complexesb |

| FRO2 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Root epidermis | Reduces soil Fe³⁺ for uptake under iron deficiencyc |

Physiological Roles of Chromate Reductases

Roles of Chromate Reductase Activity in Cellular and Environmental Protection Chromate reductase activity aids in reducing toxic

chromium species, maintaining redox balance, and detoxifying contaminated environments [73]. It overlaps with flavin reductases,

protects cells from oxidative and genotoxic stress, and reduces other toxic compounds like quinones and azo dyes, contributing to

overall cellular and environmental protection [74]. (Physiological functions of Chromate reductase is illustrated in Figure 4)

The figure summarizes the roles of quinone reductase activity in detoxification and cellular protection through xenobiotic metabolism, antioxidant defense, redox balance, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification. These processes collectively contribute to cellular protection and underpin therapeutic relevance, including applications in cancer therapy. (Source: Authors’ own work)

| Enzyme | Organism | Cofactor | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| NQO1 | Homo sapiens | FAD | Detoxifies quinones, antioxidant defense [61]. |

| ChrR | E. coli | FMN | Quinone and chromate reduction [62]. |

| YhdA | B. subtilis | FMN | Reduction of quinones, azo dyes [63]. |

| FerB | P. denitrificans | FMN | Quinone and iron reduction [64]. |

The figure summarizes the roles of quinone reductase activity in detoxification and cellular protection through xenobiotic metabolism, antioxidant defense, redox balance, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification. These processes collectively contribute to cellular protection and underpin therapeutic relevance, including applications in cancer therapy. (Source: Authors’ own work)

| Enzyme | Organism | Cofactor | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChrR | P. putida | FMN | Cr(VI), quinones, azo dyes [69]. |

| ChrR | E. coli | FMN | Cr(VI), quinones, azo dyes [70] |

| NQR | A. thaliana | FAD | Cr(VI), quinones [76] |

Discussion

The enzyme system of water nitrate and similar microorganisms, specifically Paracoccus denitrificans, is reported to be versatile in its metabolism [1, 2, 3]. NAD(P)H can hydroxymethylamine, while a flavoenzyme (such as ferA or ferB) stimulates the reaction by accepting two electrons and one proton [15,16,17,18]. The reduced forms of flavins such as FMNH₂ or FADH₂ are important electron donors for post reduction processes. They are used to entangled injury, DNA is synthesized through ribonucleotide reductase, monooxygenase oxygenates alien compounds onto the planet [29,30]; while light transformation occurs in living bioluminescent marine bacteria like Vibrio fischer [20].

Iron reductases also illustrate a general strategy of adaptation among micro-organisms. Under iron-limiting conditions, by reducing ferric iron (Fe³) to ferrous iron (Fe²), they are able efficiently obtain this side product [10,36,39,40]. That such iron reductive systems are used by quite different types of living beings (such as the FRE family in Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is proof that they are basic to life. Reducing ferric ion to ferrous is something without which it would no longer be subsistable [39,51]. PdN1FerB is a typical example of the quinone reductase. When an organism's environment is full of metal ions, this enzyme plays an important role in quenching ROS and makes them harmless and transportable by reducing quinones to hydroquinones [55,58,64]. Enzymes such as ChrR in P. putida also display enzymatic and structural similarities with reductase, so evolutionarily there are similarities between these two types. The enzymes of this group possess a wide substrate promiscuity and ecological significance, having the capability to reduce such varied substances as quinones, azo dyes, and Cr(VI) [68,69,70,72].

Conclusion

This work highlights the biochemical diversity and significance of oxidoreductase enzymes in Paracoccus denitrificans and other bacteria. Flavin, iron, quinone, and chromate reductases collectively contribute to cellular redox balance, detoxification, nutrient acquisition, and ecological adaptation. Their ability to catalyze electron transfer reactions across a wide range of substrates demonstrates remarkable metabolic flexibility and environmental importance. Beyond their physiological roles, these enzymes hold considerable promise for biotechnological applications such as the degradation of hazardous pollutants and the synthesis of valuable biochemicals. Their substrate versatility and catalytic efficiency make them strong candidates for future structural and mechanistic studies, which will deepen our understanding of microbial metabolism and support the development of innovative approaches in environmental and industrial biotechnology.

Acknowledgment

The author expresses sincere gratitude to the Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic, for providing the facilities and support necessary for this work. Special thanks to mentors for valuable discussions and insights related to the biochemical studies on oxidoreductases in Paracoccus denitrificans (denitrifying bacterium).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Martínez-Espinosa RM. Microorganisms and their metabolic capabilities in the context of the biogeochemical nitrogen cycle at extreme environments. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4228. doi:10.3390/ijms21124228.

- Maurya S, Arya C, Parmar N, Sathyanarayanan N, Joshi C, Ramanathan G. Genomic profiling and characteristics of a C1-degrading heterotrophic freshwater bacterium Paracoccus sp. strain DMF. Arch Microbiol. 2023;206:10.1007/s00203-023-03729-z.

- Mazoch J, Tesarik R, Sedlacek V, Kucera I, Turanek J. Isolation and biochemical characterization of two soluble iron(III) reductases from Paracoccus denitrificans. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:553–562. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03957.x.

- Sedláček V, van Spanning RJM, Kučera I. Ferric reductase A is essential for effective iron acquisition in Paracoccus denitrificans. Microbiology (Reading). 2009;155(4):1294–1301. doi:10.1099/mic.0.022715-0.

- Sedláček V, van Spanning RJM, Kučera I. Characterization of the quinone reductase activity of the ferric reductase B protein from Paracoccus denitrificans. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;483(1):29–36. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2008.12.016.

- Sedláček V, Ptacková N, Rejmontová P, Kučera I. The flavoprotein FerB of Paracoccus denitrificans binds to membranes, reduces ubiquinone and superoxide, and acts as an in vivo antioxidant. FEBS J. 2015;282(2):283–296.

- Sedláček V, Klumpler T, Marek J, Kučera I. The structural and functional basis of catalysis mediated by NAD(P)H:acceptor oxidoreductase (FerB) of Paracoccus denitrificans. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96262. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096262.

- Kendrew S, Harding S, Hopwood D, Marsh E. Identification of a flavin:NADH oxidoreductase involved in the biosynthesis of actinorhodin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17339–17343. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.29.17339.

- Huijbers MM, Martínez-Júlvez M, Westphal AH, Delgado-Arciniega E, Medina M, van Berkel WJ. Proline dehydrogenase from Thermus thermophilus does not discriminate between FAD and FMN as cofactor. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43880. doi:10.1038/srep43880.

- Schröder I, Johnson E, de Vries S. Microbial ferric iron reductases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27(2–3):427–447. doi:10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00043-3.

- Walsh CT. Flavin coenzymes: versatile catalysts in biochemical oxidations. Biochemistry. 1980;19(18):3990–3996.

- Vincent M, Christodoulou J, Waksman G. Flavin-dependent enzymes: mechanistic diversity and biocatalytic potential. Annu Rev Biochem. 2020;89:227–249.

- Chen H, Hopper SL, Cerniglia CE. Biochemical and genetic characterization of a flavin reductase involved in the degradation of azo dyes by Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(11):7381–7388.

- Suzuki Y, Yoshida S. Reduction of azo dyes by Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J Biosci Bioeng. 2007;103(1):14–20.

- Xiao W, Wang RS, Handy DE, Loscalzo J. NAD(H) and NADP(H) redox couples and cellular energy metabolism. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018;28(3):251–272. doi:10.1089/ars.2017.7216.

- Cooper GM. The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd ed. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2000. The mechanism of oxidative phosphorylation. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9885/

- Sedláček V, Klumpler T, Marek J, Kučera I. Biochemical properties and crystal structure of the flavin reductase FerA from Paracoccus denitrificans. Microbiol Res. 2016;188–189:9–22. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2016.04.006.

- Whitehouse DG, May B, Moore AL. Respiratory chain and ATP synthase. Elsevier eBooks. 2019. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-801238-3.95732-5.

- Čėnas N, Nemeikaitė-Čėnienė A, Kosychova L. Single- and two-electron reduction of nitroaromatic compounds by flavoenzymes: mechanisms and implications for cytotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(16):8534. doi:10.3390/ijms22168534.

- Campbell ZT, Baldwin TO. Fre is the major flavin reductase supporting bioluminescence from Vibrio harveyi luciferase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(13):8322–8328. doi:10.1074/jbc.M808977200.

- Walsh CT, Wencewicz TA. Flavoenzymes: versatile catalysts in biosynthetic pathways. Nat Prod Rep. 2013;30(1):175–200. doi:10.1039/c2np20069d.

- Lee JK, Zhao H. Identification and characterization of the flavin:NADH reductase (PrnF) involved in a novel two-component arylamine oxygenase. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(23):8556–8563. doi:10.1128/JB.01050-07.

- Horstmeier HJ, Bork S, Nagel MF, Keller W, Sproß J, Diepold N, Ruppel M, Kottke T, Niemann HH. The NADH-dependent flavin reductase ThdF follows an ordered sequential mechanism though crystal structures reveal two FAD molecules in the active site. J Biol Chem. 2025;301(2):108128. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2024.108128.

- Manenda MS, Picard MÈ, Zhang L, Cyr N, Zhu X, Barma J, Pascal JM, Couture M, Zhang C, Shi R. Structural analyses of the group A flavin-dependent monooxygenase PieE reveal a sliding FAD cofactor conformation bridging OUT and IN conformations. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(14):4709–4722. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA119.011212.

- Van Den Heuvel RH, Westphal AH, Heck AJ, Walsh MA, Rovida S, Van Berkel WJ, Mattevi A. Structural studies on flavin reductase PHEA2 reveal binding of NAD in an unusual folded conformation and support a novel mechanism of action. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(13):12860–12867. doi:10.1074/jbc.m313765200.

- Nishiyama M, Birktoft JJ, Beppu T. Alteration of coenzyme specificity of malate dehydrogenase from Thermus flavus by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4656–4660.

- Deller S, Macheroux P, Sollner S. Flavin-dependent quinone reductases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(1):141–160. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7300-y.

- Elledge SJ, Davis RW. Two genes differentially regulated in the cell cycle and by DNA-damaging agents encode alternative regulatory subunits of ribonucleotide reductase. Genes Dev. 1990;4(5):740–751. doi:10.1101/gad.4.5.740.

- Chenprakhon P, Wongnate T, Chaiyen P. Monooxygenation of aromatic compounds by flavin-dependent monooxygenases. Protein Sci. 2019;28(1):8–29. doi:10.1002/pro.3525.

- Cline TW, Hastings JW. Bacterial bioluminescence in vivo: control and synthesis of aldehyde factor in temperature-conditional luminescence mutants. J Bacteriol. 1974;118(3):1059–1066. doi:10.1128/jb.118.3.1059-1066.1974.

- The potential of siderophores in biological control in plant diseases. 2025. doi:10.56669/hgrs2291.

- Torrents E. Ribonucleotide reductases: essential enzymes for bacterial life. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:52. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2014.00052.

- Torres Pazmiño DE, Winkler M, Glieder A, Fraaije MW. Monooxygenases as biocatalysts: classification, mechanistic aspects and biotechnological applications. J Biotechnol. 2010;146(1–2):9–24. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.01.021.

- Brodl E, Winkler A, Macheroux P. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial bioluminescence. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2018;16:551–564. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2018.11.003.

- Tsylents U, Burmistrz M, Wojciechowska M, Stępień J, Maj P, Trylska J. Iron uptake pathway of Escherichia coli as an entry route for peptide nucleic acids conjugated with a siderophore mimic. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1331021. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2024.1331021.

- Valiauga B, Williams EM, Ackerley DF, Čėnas N. Reduction of quinones and nitroaromatic compounds by Escherichia coli nitroreductase A (NfsA): characterization of kinetics and substrate specificity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017;614:14–22. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2016.12.005.

- Nivière V, Fieschi F, Dećout JL, Fontecave M. The NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductase from Escherichia coli: evidence for a new mode of binding for reduced pyridine nucleotides. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(26):18252–18260. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.26.18252.

- Nijvipakul S, Wongratana J, Suadee C, Entsch B, Ballou DP, Chaiyen P. LuxG is a functioning flavin reductase for bacterial luminescence. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(5):1531–1538. doi:10.1128/JB.01660-07.

- O'Neill AG, Beaupre BA, Zheng Y, Liu D, Moran GR. NfoR: chromate reductase or flavin mononucleotide reductase? Appl Environ Microbiol. 2020;86(22):e01758-20. doi:10.1128/AEM.01758-20.

- Cain TJ, Smith AT. Ferric iron reductases and their contribution to unicellular ferrous iron uptake. J Inorg Biochem. 2021;218:111407. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2021.111407.

- Wairich A, Aung M, Ricachenevsky F, Masuda H. You can’t always get as much iron as you want: how rice plants deal with excess of an essential nutrient. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1381856. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1381856.

- Ratheesh A, Sreelekshmy B, Namitha S, Sasidharan S, Nair KS, George S, Shibli S. Regulation of extracellular electron transfer by sustained existence of Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ redox couples on iron oxide-functionalized woody biochar anode surfaces in bioelectrochemical systems. Surf Interfaces. 2024;105114. doi:10.1016/j.surfin.2024.105114.

- Boswell-Casteel RC, Johnson JM, Stroud RM, Hays FA. Integral membrane protein expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1432:163–186. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-3637-3_11.

- Marques HM. The bioinorganic chemistry of the first row D-block metal ions—an introduction. Inorganics. 2025;13(5):137. doi:10.3390/inorganics13050137.

- Bruice TC. Mechanisms of flavin catalysis. Acc Chem Res. 1980;13(8):256–262.

- Macheroux P, Kappes B, Ealick SE. Flavogenomics—a genomic and structural view of flavin-dependent proteins. FEBS J. 2011;278(15):2625–2634. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08202.x.

- Andrews SC, Robinson AK, Rodríguez-Quiñones F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27(2–3):215–237. doi:10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00055-X.

- Hider RC, Kong X. Chemistry and biology of siderophores. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27(5):637–657. doi:10.1039/b906679a.

- Miethke M, Marahiel MA. Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71(3):413–451. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00012-07.

- De Luca NG, Wood PM. Iron uptake by fungi: contrasted mechanisms with internal or external reduction. Adv Microb Physiol. 2000;43:39–74. doi:10.1016/S0065-2911(00)43002-X.

- Eide D, Davis-Kaplan S, Jordan I, Sipe D, Kaplan J. Regulation of iron uptake in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the ferrireductase and Fe(II) transporter are regulated independently. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(29):20774–20781.

- Connolly EL, Campbell NH, Grotz N, Prichard CL, Guerinot ML. Overexpression of the FRO2 ferric chelate reductase confers tolerance to low-iron conditions and reveals posttranscriptional control. Plant Physiol. 2003;133(3):1102–1110. doi:10.1104/pp.103.025122.

- Wermuth B, Platts KL, Seidel A, Oesch F. Carbonyl reductase provides the enzymatic basis of quinone detoxication in man. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35(8):1277–1282. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(86)90271-6.

- Ross D, Siegel D. Functions of NQO1 in cellular protection and CoQ10 metabolism and its potential role as a redox-sensitive molecular switch. Front Physiol. 2017;8:595. doi:10.3389/fphys.2017.00595.

- Bolton JL, Dunlap T. Formation and biological targets of quinones: cytotoxic versus cytoprotective effects. Chem Res Toxicol. 2017;30(1):13–37. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00256.

- Eschenbrenner M, Covès J, Fontecave M. The flavin reductase activity of the flavoprotein component of sulfite reductase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(35):20550–20555. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.35.20550.

- Binter A, Staunig N, Jelesarov I, Lohner K, Palfey BA, Deller S, Gruber K, Macheroux P. A single intersubunit salt bridge affects oligomerization and catalytic activity in a bacterial quinone reductase. FEBS J. 2009;276(18):5263–5274. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07222.x.

- Cassagnes LE, Perio P, Ferry G, Moulharat N, Antoine M, Gayon R, Boutin JA, Nepveu F, Reybier K. In cellulo monitoring of quinone reductase activity and reactive oxygen species production during the redox cycling of 1,2- and 1,4-quinones. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;89:126–134. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.07.150.

- Ross D, Siegel D. The diverse functionality of NQO1 and its roles in redox control. Redox Biol. 2021;41:101950. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2021.101950.

- Oh ET, Park HJ. Implications of NQO1 in cancer therapy. BMB Rep. 2015;48(11):609–617. doi:10.5483/bmbrep.2015.48.11.190.

- Yuhan L, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A. Impact of NQO1 dysregulation in CNS disorders. J Transl Med. 2024;22:4. doi:10.1186/s12967-023-04802-3.

- Eswaramoorthy S, Poulain S, Hienerwadel R, Bremond N, Sylvester MD, Zhang YB, Berthomieu C, Van Der Lelie D, Matin A. Crystal structure of ChrR—a quinone reductase with the capacity to reduce chromate. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36017. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036017.

- Bibi S, Breeze CW, Jadoon V, et al. Isolation, identification, and characterization of the malachite green detoxifying bacterial strain Bacillus pacificus ROC1 and the azoreductase AzrC. Sci Rep. 2025;15:3499. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-84609-4.

- Sedláček V, van Spanning RJ, Kucera I. Characterization of the quinone reductase activity of the ferric reductase B protein from Paracoccus denitrificans. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;483(1):29–36. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2008.12.016.

- Sharma P, Singh SP, Parakh SK, Tong YW. Health hazards of hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) and its microbial reduction. Bioengineered. 2022;13(3):4923–4938. doi:10.1080/21655979.2022.2037273.

- Mala JGS, Sujatha D, Rose C. Inducible chromate reductase exhibiting extracellular activity in Bacillus methylotrophicus for chromium bioremediation. Microbiol Res. 2015;170:235–241. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2014.06.001.

- Park CH, Keyhan M, Wielinga B, Fendorf S, Matin A. Purification to homogeneity and characterization of a novel Pseudomonas putida chromate reductase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66(5):1788–1795. doi:10.1128/AEM.66.5.1788-1795.2000.

- Tong Y, Kaya SG, Russo S, Rozeboom HJ, Wijma HJ, Fraaije MW. Fixing flavins: hijacking a flavin transferase for equipping flavoproteins with a covalent flavin cofactor. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;145(49):27140–27148. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c12009.

- Gonzalez CF, Ackerley DF, Lynch SV, Matin A. ChrR, a soluble quinone reductase of Pseudomonas putida that defends against H₂O₂. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(24):22590–22595. doi:10.1074/jbc.m501654200.

- Biniek C, et al. Role of the NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase NQR and cytochrome b AIR12 in controlling superoxide generation at the plasma membrane. Planta. 2017;245:807–817. doi:10.1007/s00425-016-2643-2.

- Jomova K, Raptova R, Alomar SY, Alwasel SH, Nepovimova E, Kuca K, Valko M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: chronic diseases and aging. Arch Toxicol. 2023;97(10):2499–2574. doi:10.1007/s00204-023-03562-9.

- Zhou Z, Zhu L, Dong Y, You L, Zheng S, Wang G, Xia X. Identification of a novel chromate and selenite reductase FesR in Alishewanella sp. WH16-1. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:834293. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.834293.

- Sandana Mala JG, Sujatha D, Rose C. Inducible chromate reductase exhibiting extracellular activity in Bacillus methylotrophicus for chromium bioremediation. Microbiol Res. 2015;170:235–241. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2014.06.001.

- Russ R, Rau J, Stolz A. The function of cytoplasmic flavin reductases in the reduction of azo dyes by bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66(4):1429–1434. doi:10.1128/AEM.66.4.1429-1434.2000.

- Liu G, Zhou J, Fu QS, Wang J. The Escherichia coli azoreductase AzoR is involved in resistance to thiol-specific stress caused by electrophilic quinones. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(20):6394–6400. doi:10.1128/JB.00552-09.

- Bironaite D, Anusevicius Z, Jacquot JP, Cenas N. Interaction of quinones with Arabidopsis thaliana thioredoxin reductase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1383(1):82–92. doi:10.1016/S0167-4838(97)00190-8.